Coney Island as It Was in September 2019

Water has always played a part in Coney’s destiny.

Coney Island's river landing.

It was the water of the Ohio that carried the Guiding Star and its first guests to “Ohio Grove, Coney Island of the West” in 1886. Those anxious to escape the noise and commotion of the Queen City had already been coming here for nearly two decades, though. To the dance hall, the bowling alley—to James Parker’s property and the apple orchard that he realized made more money as a rentable picnic grove than farmland.

The grove was so popular that two steamboat captains bought it from Parker and began ferrying passengers from the city to the shore. They first added “Coney Island” simply as a reference to the famed New York attraction, but ended up adopting the name as their own.

And it stuck.

Coney's river gate.

Coney followed the prototypical path of so many early American amusement parks—the ones that evolved from rural leisure areas into resorts while welcoming the latest tastes in entertainment and popular culture. As owners and management came and went, so did the first Island Queen—steaming along the Ohio River and bringing more and more guests to “America’s Finest Amusement Park.”

The first Island Queen in 1906. Image via the Library of Congress.

In the eyes of many, the park had certainly deserved that self-imposed title when it first appeared in 1926. It had been just one year since the park had added a slew of thrilling rides and the second Island Queen began sailing on the Ohio. Their marquee attraction of the time, though, was one based around water.

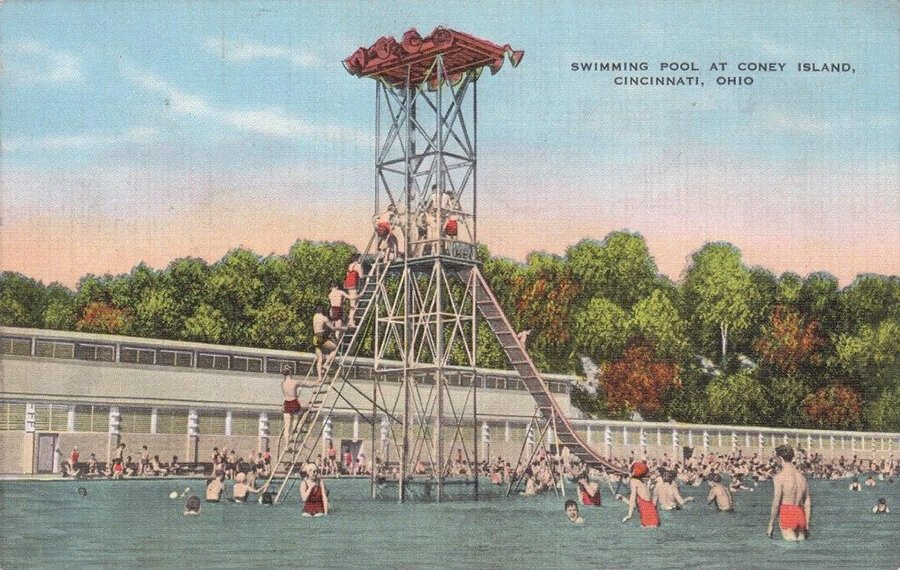

Vintage postcard of Sunlite Pool. Image via Pinterest.

Sunlite Pool was one of the world’s largest recirculating bodies of water when it opened in 1925. It's still one today. It helped further cement Coney Island’s status as a Cincinnati institution alongside the park’s thundering wooden roller coasters and midways lined by carnival barkers. But the water of the Ohio was still there, rising each Spring in the way it was known to do.

Sometimes it was just a nuisance.

Other times it was devastating.

Like in 1937 when water rose 28 feet above the park and consumed much of Downtown Cincinnati, as well as, several other communities between Pittsburgh and Cairo, Illinois.

Flood marker within Coney Island.

Still, Coney Island persisted.

Come hell, literal high water, or the Great Depression, "America’s Finest Amusement Park" reopened right on schedule for 1938. And it seemingly maintained that fine reputation, so much so that Walt Disney himself visited in 1953 to gain some inspiration for the iconic park he would soon build—just two years before civil rights icon Marian Spencer led the charge to desegregate Coney in 1955 (Sunlite Pool would not be integrated until 1961).

Crowds and new attractions kept coming. So did the river. Two replica steam locomotives began circumventing the park’s lake in 1963, just before another strong flood engulfed the park in the Spring of 1964.

Coney Island's midway and Shooting Star roller coaster during the park's heyday. Image via Pinterest.

Times were changing. Walt Disney had seen to that when he revolutionized the amusement industry in 1955. He was about to do it again with a second, larger park in Florida.

Coney, on the other hand, was out of space.

Both for new rides and for more parking to accommodate the automobiles that had replaced the steamboats and streetcars. A proposed competitor loomed on the horizon, supposedly planned to spring up in nearby Northern Kentucky where the interstates converged. And the river—the river kept paying its annual Springtime visits. Coney’s owners looked for new investors who could potentially facilitate the dream of relocation.

The park's picnic grove is named in honor of the institution's original name, Parker's Grove, while the shelters are named after defunct attractions such as the "Land of Oz."

Cincinnati’s Taft Broadcasting Corporation was interested in entering the amusement industry. They were one of many enterprising corporations and individuals across the United States who sought to replicate Disney’s success with destinations of their own. They completely purchased Coney Island in 1969.

Historic view of Coney Island. Image via Pinterest.

Rather than rebuild Coney brick-for-brick, the broadcasters planned to open an entirely new amusement resort north of the city, just off a relatively new interstate that offered easy automobile access to other population centers. Kings Mills, Ohio would see several of Coney’s rides, policies, staff, attractions, and traditions reborn on a grander and larger scale when Kings Island opened in 1972. With a full-service hotel, campground, golf courses, zoo, and state-of-the art amusement park (one stocked with brand new rides in addition to the classics that made the trip from Coney), this new park even featured an entire area themed in recognition of its historical predecessor. And the river by this new park never threatened a flood.

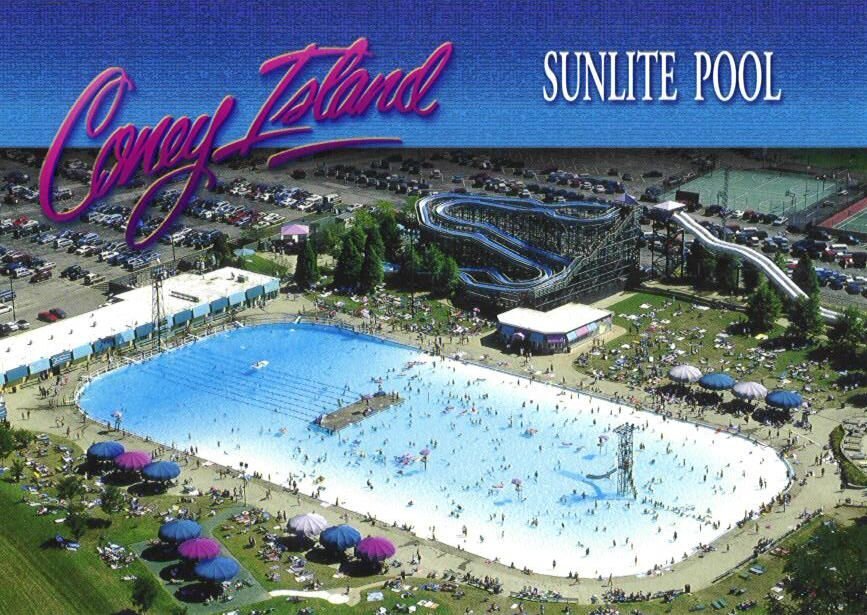

Much of what had remained at “Old Coney” met the wrecking ball, but not Sunlite Pool. It was far too big and expensive to replicate such an iconic attraction up north. So Taft kept it open. Even as their corporate ambitions led them to open new parks across the United States, Canada, and Australia—Sunlite’s water still provided a cool summer respite for swimmers on Cincinnati’s East Side.

1980s era view of Coney's Sunlite Pool. Image via Pinterest.

Over the ensuing years, “Old Coney” received the occasional new attraction—a private tennis club, the reopening of its picnic grove, a Ferris wheel, and an outdoor amphitheater to serve as a summer home for touring musical acts, as well as, the Cincinnati Symphony and Pops Orchestras.

Taft, Kings Island, and the entire new chain of parks birthed from the inspiration of Coney Island, eventually went their own separate way. A man named Ronald Walker came to purchase Coney and he brought with him a handful of classic, small rides over the next few years in addition to a multi-million dollar renovation of Sunlite Pool. The river was still there, being dramatic once more in 1997, but Coney slowly grew back into a full fledged amusement park—although one much smaller than it had been in its heyday. Still, it was a fun and welcoming spot for families and guests who wanted to visit a place that wasn’t as corporate as Coney’s descendant up north.

Plaque commemorating the 1997 flood within the park.

And for years, the combination of Sunlite Pool with a collection of carnival-style rides, classic games, live entertainment, and a few other attractions sprinkled in—seemed to work just fine, no matter how much the river acted up. Even when it did so again in 2018.

Markings of various flood heights within the park over the years.

But then, in the Fall of 2019, Coney announced that it would be removing its rides at the end of the season. Water was the announced reason, the water in Sunlite Pool.

“All of our consumer research, all of our consumer feedback, and all of our in-park data shows that the vast majority of our guests come to Coney Island because of the fun they have while in the Sunlite Pool area.”

That’s what Park President Rob Schutter Jr. said in a press release which explained the park’s reasoning to focus further investment solely on its water attractions. A decision that would cause the layoff of 13 full-time and 272 seasonal positions, many of them occupied by passionate employees who had been there for years.

And so, I went to Coney Island to document how the park looked before all the rides disappeared.

A magician performs on the Moonlite Gazebo Stage.

Pedal boats on Lake Como.

Boat dock, Lake Como.

Moonlite Square Games of Skill.

Moonlite Square Games of Skill.

Scrambler.

The Tempest.

River Runner.

Sign for the Flying Bobs.

Lighting on the Dodgems.

Wipe Out.

Top Spin.

Tilt-a-Whirl.

Lighting fixture on Wipe Out.

Rock-O-Plane.

Ferris Wheel.

Freshly made corn dogs.

Back when I still worked in the amusement industry, I had heard a rumor from multiple sources. The story went that Coney was actively pursuing the construction of a wooden roller coaster from a modern manufacturer. The new medium sized ride would cater to both children and adults, rumbling “out-and-back” in classic fashion around the park’s lake.

Rides on the shore of Lake Como.

Had it been built, it would’ve brought the historical park not just another attraction, but something that would’ve continued to harken back to Coney’s halcyon days and further cement its place as not just a local institution, but the kind of amusement park now rarely seen across the American landscape.

Sadly, it never came to be.

Coney's historic Moonlite Gardens.

In his 2002 book, “Cincinnati’s Coney Island,” Charles J. Jacques Jr. wrote:

“Coney is like Cincinnati—a wonderful mixture of old and new. It has always been a place of abundant laughter. From the moment James Parker decided to rent his grove out for music, dancing, and other innocent amusement, the site has helped lift the spirit of Cincinnatians.”

The park's museum.

Footnotes:

In 1996, Ronald Walker purchased Americana/LeSourdsville Lake in Middletown, Ohio (just 5 years after he bought Coney Island), and created the Park River Corporation. Walker passed away in 1997 and by 2000, Americana was sold to Jerry Couch. The Middletown park was closed for 2000 and 2001, but reopened for a single season in 2002 before closing permanently. That park’s story and its demise was the first topic ever covered here on QC/D and it’s been covered again several times since.

A few of Coney Island’s children rides were sold to the local Cincinnati Circus Company and will be available for rental/special events. The rest of the rides are currently for sale, but Kings Island has already dissuaded the idea that they will be purchasing any of them.

One of Coney’s marquee attractions was the Rock-O-Plane. The ride originally hailed from Americana/LeSourdsville Lake and was built by the Eyerly Aircraft Company. Eyerly had originally built devices that could train pilots before shifting to the amusement industry. Coney's Tempest also came from Americana.

Coney’s second Tilt-A-Whirl (the one seen in the photographs of this post) came from the defunct Fantasy Farm amusement park in Middletown, Ohio. Fantasy Farm bordered Americana/LeSourdsville Lake and was covered in a January 2019 QC/D post.

I’ve heard before that during Coney’s days under the Park River Corporation, both it and Americana were in a marketing partnership with Surf Cincinnati—a defunct water park that has also been covered extensively here on QC/D.

Several QC/D articles over the years have dealt with exploring the abandoned remains of amusement parks across the American Midwest. You can find all those stories here.

While the post here only briefly skims Coney’s vast history, ConeyIslandCentral.com features both extensive and thoughtful coverage of the park. It’s well worth visiting and has been authored by a longtime employee of the park and friend. A few years back, I shot his engagement photographs within Coney.

In addition to Coney Island Central, "Cincinnati’s Coney Island" by Charles J. Jacques Jr. (published 2002) is an excellent read.

A few of Kings Island’s current rides (as of this post) originated from Coney Island. They are the Scrambler, Monster, Log Flume (now known as "Race for Your Life Charlie Brown"), and Kiddy Whip (now known as "Linus’ Beetle Bugs"). The "Peanuts Off-Road Rally" also hailed from Coney, but has been modified extensively over the years. The Sky Ride, Tumblebug, and Rotor were relocated to Kings Island, but were eventually removed from the newer park.

Special thanks to friends (and fellow Kings Island veterans) Robbie Zerhusen and Tyler Mullins for their help with this article.

Update | Jan. 3, 2024:

When I first published these photographs and words in 2019, the theme of Coney’s story was “water.” Now, nearing what appears to be its true and final demise, however, water isn’t the reason. Yet, as the above quote from Charles J. Jacques Jr.’s book laid out: Coney will seemingly still be a place that can “…lift the spirit of Cincinnatians.”

On December 14, 2023, it was announced that Coney Island and Sunlite Pool would be closing permanently. The reason given was the park’s pending purchase by Music and Event Management, INC. (MEMI) and their intention to build a new music venue on the site that’s estimated to cost $118 million.

MEMI, a subsidiary of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, has owned and operated two existing music venues (Riverbend and PNC Pavillion) nearby for several years. Their latest addition is intended to be a new complement to the existing stages with the stated goal of creating a “live music campus.”

How much the new “campus” will incorporate Coney’s historic structures—such as Moonlight Gardens and the entrance gates—is yet to be known, but it appears that Sunlite Pool is headed for the wrecking ball. The announcement managed to draw the ire of social media users who were lamenting the loss of a piece of local history. Which brings me to this update.

In years prior, my work focused almost exclusively on the history of Cincinnati. I also spent a large part of my youth working at Coney’s successor: Kings Island. The closure of Coney Island is certainly a significant event, but I believe it’s fair to say that the park of yesteryear—the one remembered in the postcards seen below and the images of history books—was dead long before December 14, 2023. Hell, it was dead well before the “second wave” of rides were removed in 2019. “Old Coney” truly was lost in the Spring of 1972 as soon as Kings Island opened its gates.

Yes, the pool still stuck around for over fifty years afterwards and attempts were made to make the place an “amusement park” once more, but let’s just be honest: none of that was the same as “Old Coney.” Even someone like me who deeply appreciates local history (and who was born well after the original park’s closure, yet would’ve loved to have experienced it) could see the writing on the wall. Still, I acknowledge that there are numerous people who have fond memories of the Coney Island that was from 1972-2023. Many of them are my friends.

I also want to acknowledge that I didn’t write this to carry water for MEMI. Their Riverbend venue is terrible, PNC Pavillion isn’t much better, and the company managed to kill the best music festival this city ever had. Maybe, though, this new venue will be a step in the right direction, a better experience for music fans. Perhaps it’ll even lure in acts other than the Mötley Crües and Def Leppards of the world. The ones who pop up every few years to remind us: they’re still alive and they still suck.

In the end, maybe “Coney Island” will still be an area for great amusement and fun.

A few postcards I grabbed from The Ohio Book Store after the news of Coney’s closure broke: