The Dinosaurs of Local Libraries

I don’t really remember how the idea for this post came about, but I’d known about Stegowagenvolkssaurus from my time as a student at Northern Kentucky University. No matter how (in)frequently one made use of the library, it was impossible to miss the hulking hybrid of dinosaur and iconic car that would easily stand out in any art museum, let alone among monotonous rows of books. It wasn’t until years after I graduated, though, that I realized there was another half-reptile, half-vehicle adorning another local literary institution of higher education. I wanted to photograph and put together a story that I described in my notes as: “A quick, fun piece, focusing on the libraries of two universities and their interesting sculpture connection.” I wasn’t the first to have that idea, though.

There was no way I really could be. These sculptures were made by an acclaimed, well-known artist. One whose career has been celebrated and honored for numerous achievements, not just these two prehistoric-inspired pieces. Perhaps one of the best examples of media which has chronicled the life and work of the late Patricia Renick comes from Cedric Rose and Cincinnati Magazine in 2017. I’m a bit biased because Cedric is an awesome friend and even appeared in my Waffle House stories, but in all sincerity: his writing and ability to tell a story are second-to-none. So, I’m not going to rip him off here. Rather, I’ll give a quick summary and encourage anyone who comes across my corner of the internet to go read Ced's wonderful piece about the “monumental” Patricia Renick.

• • •

A native of Florida, Patricia A. “Pat” Renick was born in 1932. In high school, she met her longtime companion Laura Chapman and the two would go on to attend Florida State University. While majoring in Art Education, Renick began to make lasting impressions with her art in the dorms before graduating with honors in 1954. She’d go on to become a high school teacher until a series of traumatic medical misdiagnoses nearly destroyed her life.

After recovering, Renick made her way to Miami where she became engrained in the city’s art scene and made a fateful connection with visiting French student Claude Perpere. After spending two years in Europe to study, travel, work, and visit Perpere—Renick returned to the U.S. and enrolled in Ohio State University’s MFA sculpture program. Upon graduation, she accepted a teaching role with the University of Cincinnati’s College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning (DAAP) in 1970.

Renick’s personal artistic pursuits continued as she began establishing herself as a professor on UC’s campus. Gleaning inspiration from model kits sold “at a toy counter in a dime store,” she pieced together a dinosaur and car model that became the basis for a massive artwork. A response to the global oil crisis of the time, Stegowagenvolkssaurus was a monumental undertaking that required Renick to collaborate with numerous partners and learn new techniques. At the last minute, the giant sculpture had to be re-engineered so that it could be properly transported into the Cincinnati Art Museum in 1974. The piece was well received, made national press, and was also put on display in Chicago. Stegowagenvolkssaurus helped establish Renick’s name at a time when she was also becoming known for her educational acumen, as well as, for challenging of the status-quo in male dominated academia.

Decades later, Stegowagenvolkssaurus would be completely restored and donated to Northern Kentucky University just across the state line from downtown Cincinnati. Today, it resides in the school’s W. Frank Steely Library.

Just one year after Stegowagenvolkssaurus debuted at the Cincinnati Art Museum, a flatbed truck pulled up to Renick’s home a few miles away. There, it dropped off a retired U.S. Army helicopter for the artist’s next ambitious undertaking.

Public domain photograph of a YOH-6A Cayuse prototype in flight. From the U.S. Department of the Army publication Vietnam Studies - Airmobility 1961-1971.

The OH-6 Cayuse may not be as iconic as the “Huey,” but the light helicopter was also a fixture in the skies of the Vietnam War. Introduced in 1966, the single engine aircraft was immediately pressed into service as a reconnaissance and bait platform that would attempt to evade and draw out enemy fire before marking those positions as targets for larger, deadlier weapons. The use of the Cayuse in its “hunter-killer” role became a hallmark of American war tactics and variants of the chopper are still produced today for both the civilian and military markets.

With the help of students and donors, supplies were secured and the helicopter was relocated to the former Strietmann Biscuit factory in Cincinnati’s Over-The-Rhine neighborhood. The particular Cayuse that Renick received had been damaged in the war and it’s reported that the National Guard helped her source replacement parts to reconstruct the tail section.

After two years of work, Triceracopter: The Hope for the Obsolescence of War debuted at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center in 1977. Alongside it was another piece: She Became What She Beheld, a self-portrait depicting Renick as a triceratops clutching her original model for the work.

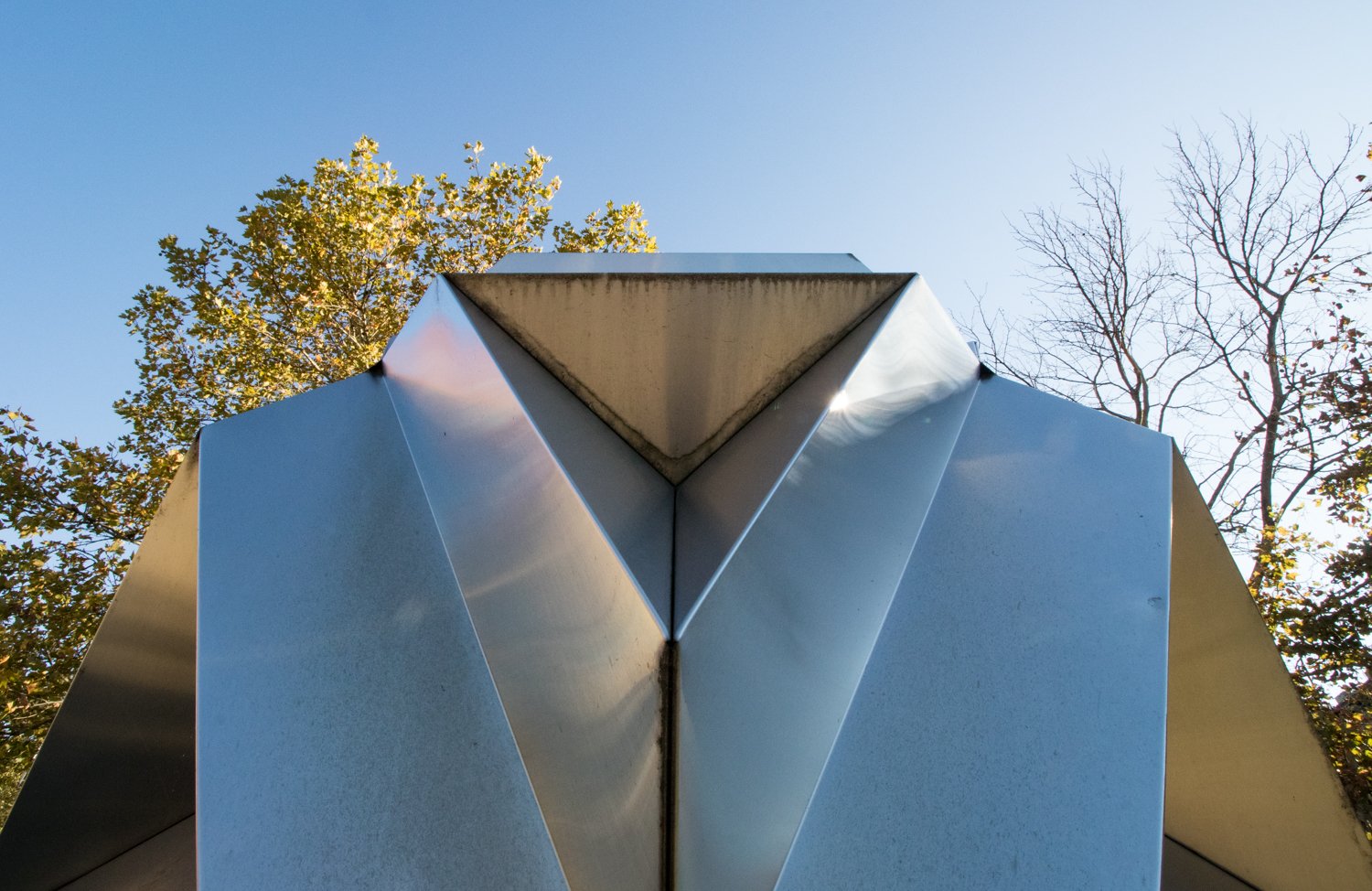

Like Stegowagenvolkssaurus a few years before it, Triceracopter was well received for its ambitious undertaking, message, innovative use of materials, and detailed attention to technique. In 2010, the piece was donated to the University of Cincinnati and installed in the school’s central Walter C. Langsam Library. Renick’s self portrait was placed nearby and a contextual exhibit telling the story of both the piece and Renick’s career were also installed.

The aforementioned Cedric Rose sums up both of Renick’s iconic sculptures well in his 2017 essay:

“They warn. And they play to the kid in us, these works, these giant toys that are the stuff of nightmares, sci-fi time travelers nesting amid the Brutalist modern campus architecture. We’re fragile beings in a room with monsters, they seem to say. And they have the power to show us the monsters we harbor inside.”

Pat Renick’s career is remembered for much more than just these two pieces which combined “the biological with the mechanical.” In both the the sculpted and written form, she’d go on to chronicle the medical malpractice and trauma that nearly killed her. In addition to being a groundbreaking force on the local university’s staff, Renick would host the “National Sculpture Conference: Works by Women” in Cincinnati. The event would bring several notable artist appearances, lectures, and gallery showings to the Queen City for 1987.

The former Strietmann Biscuit Factory which once held Renick’s studio.

After Renick was forced out of her workspace in the old biscuit factory (which was eventually renovated into modern office space and even a coffee shop), she partnered with other local artists to establish a studio in the city’s Brighton neighborhood.

A section of Cincinnati’s Brighton neighborhood featuring its countless murals. Looming in the background is The Mockbee, a venue for live music and gallery showings.

While there, the story goes that she encouraged the city to create better access to the area. Once again from Cedric Rose:

“Renick petitioned the city to have a [vehicular connection] put in…the move was part of her local installation of ’30-Module Sphere,’ which she designed for a sculpture exhibition at Chicago’s Navy Pier and had been built by Brighton metal fabrication company Young & Bertke.”

30-Module Sphere remains in Brighton today—a neighborhood that still serves as an enclave for artists among the city’s industrial past and on the borders of gentrification below the hill where Renick once lived and taught.

What appears to be damage from a bullet at the base of 30-Module Sphere.

Patricia Renick would pass away in 2007 after a celebrated career as both an artist and educator. Laura Chapman—who had been Renick’s companion, partner, and confidante since the two were in high school—would go on to donate both Stegowagenvolkssaurus and Triceracopter to the universities they now reside within. She had been a driving force in meticulously documenting Renick’s process over the years, one of the key reasons that the public is still able to have such insight into the life of artist Patricia Renick. Sadly, Chapman would pass away in 2021.

I can’t recommend Cedric’s essay enough. It’s truly a beautifully told story about the life of an incredible artist and human being—one that goes into far more detail than what’s found here. There’s also an interesting personal connection he had with Renick that’s recalled early on in his writing:

“I met Renick once, briefly, in the mid-1990s. My roommate Ryan was a student in her Issues in Contemporary Art class. He knew that I wanted a cat and she needed someone to adopt a kitten. One day Renick swept from a car wearing a camel coat and one of the flamboyant, broad-brimmed boaters for which she was known, handed me a kitten and some cat accoutrement, said, ‘Have fun,’ and disappeared. It was only much later, in 2014, seven years after her death, that I really felt like I got to know her.”

Cedric’s work with the University of Cincinnati made him aware of Renick’s legacy and in 2017 he went on to author the article that has been frequently referenced here. Which—much like Chapman’s documentation and generosity—serves as a lasting tribute to not just a local legend, but a legend of the art world as well.

If you enjoyed this story, you might also enjoy the one about Stuart Fink, another Cincinnati sculptor, and one of his creations: Circumspect.

Since 2007, the content of this website (and its former life as Queen City Discovery) has been a huge labor of love.

If you’ve enjoyed stories like The Ghost Ship, abandoned amusement parks, the Cincinnati Subway, Fading Ads, or others over the years—might you consider showing some support for future projects?