Two Nights at the Oakland Coliseum

There’s a unique feeling that comes over oneself when engaging in recreational trespassing. Heightened senes of caution and danger elicit strong responses of anxiety and hesitation. Emotions that would completely overwhelm were it not for the calm-inducing curiosity of one’s surroundings.

You’re not supposed to be here.

Which means: you’re somewhere.

When I had that familiar feeling of illicit adventure recently, though, I hadn’t been looking for it. I’d simply gone up some stairs to find myself in one of the stadium’s upper concourses. A liminal void where the restrooms were open, but the concession stands were shuttered. No other person in sight, section after section, until I eventually saw an usher. Flagging him down with a well-practiced Midwestern courtesy wave, I asked: “Am I allowed to be up here?”

“You sure are,” he said with a laugh and a smile. “Welcome to the Oakland Coliseum.”

My view from the upper deck of the Oakland Coliseum on the evening of August 20, 2024.

Throughout my urban exploration work, I’ve documented several abandoned sports facilities. From indoor arenas to football stadiums, two have even been ballparks. The Oakland Coliseum, however, was not abandoned when I paid the place a visit on a Tuesday night in August 2024. As the usher and I spoke, we overlooked a facility that was just minutes away from the first pitch of a Major League Baseball game. The Athletics were well out of playoff contention, facing a middling Tampa Bay squad, and had long ago destroyed what little good will they had left with fans, but still—the turnout was low. Shockingly low. Less than a thousand if I had to guess (4,377 if the official figure was to be believed).

Although the 8/20/24 game was advertised as a “Bark! at the Ballpark” night, I never actually saw a dog. I did hear several barks and howls echo throughout the cavernous building while watching the game, though.

A stereotypically beautiful California evening was in full effect, lighting the concourse with a cinematic warmth. I’d been smitten with this place as soon as I’d stepped off the train, but now I was falling in love. What sent me head-over-heels, though, was the seat I grabbed just as the game got underway. One centered behind home plate in the very last row of the uppermost, nose-bleed deck. A spot where I was both perfectly situated to not only compose a photograph, but also meet so many other interesting people who’d eventually stroll by to do the same exact thing. Some were longtime fans getting one last glimpse of the team, and a few were like me: visiting for the novelty. Everyone was there for baseball, though.

Most of the seats may have been empty, but those still bothering to attend the A’s final season were making their presence known. The most minute plays were rewarded with cheers while umpires were met with justified vulgarity. Sound, in the Coliseum, can carry. Even when “no one” is there.

I know that, because I could plainly hear major league players scream “I got it” all the way up where I sat (which means the players and umpires could absolutely hear the dudes a few sections over express their feelings). This building must’ve been incredible when the stands were full and the home teams were doing well. Not just baseball’s Athletics, but also the National Football League’s Raiders—the other Oakland team that’d already left for Vegas.

This hallway immediately brought back memories of attending games at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati as a kid.

One hallmark of the Coliseum’s age are the bundles of modern wires and data cables strung seemingly everywhere. In this case: directly above a concession stand.

Massive renovations in the mid-1990’s brought climate-controlled club seating and luxury boxes to the Coliseum—a stark contrast from the building’s original, utilitarian aesthetic. Rarely used for Athletics games, though, this area of the stadium has the charm of a dead mall or empty convention center.

Old-school urinals in an upper deck restroom.

A row of seats hints at the facility’s various color schemes from over the years.

If I was being honest in that moment (and now): I didn’t see what the problem was. The Oakland Coliseum was old, but being a particular type of old was what gave the Coliseum its distinctive identity. It’s not just the last of its kind, it really is one-of-a-kind. A hybrid structure of nostalgia pieced together over a rapidly evolving American sports landscape at the crossroads of culture and politics.

The skyline of Oakland as seen from the Coliseum’s upper deck.

The skyline of of San Francisco as seen from the Coliseum’s upper deck.

The neighboring Oakland Arena can be seen on the left.

More cables.

The pedestrian bridge which connects the Coliseum with nearby train stations.

If the Athletics ownership ever had any guts, they would’ve embraced what the fans had long ago accepted: that the place was truly “baseball’s last dive bar.” A distinction not only deserved and representative of a proud city, but one that should’ve been celebrated. It took only one inning, and a seagull landing in an empty seat near me, to truly understand.

. . .

I won’t pretend to possess more than a basic understanding of the cultural zeitgeist surrounding the geography of California’s Bay Area—a region where three major American cities reside within close proximity to one another. However, I believe it’s fair to say that San Francisco rose to prominence first (at least in the sense of an average person having an awareness of its existence). As time went on and the population of the greater-Bay Area continued to explode, though, the nearby cities of Oakland and San Jose would seek to establish distinct identities of their own.

They weren’t the only urban centers chasing this kind of recognition. As a booming population took hold within the prosperity of Post-World War Two America, cities jockeyed for position within the ranks of a new economic order. No longer would the national reputation rest squarely on the shoulders of a handful of established, older cities—but rather: a map of metropolitan centers from coast to coast. And luring a professional sports team was often seen as one way to instantly place your city on that map. The various leagues of various games offered varying degrees of prestige, but none came close to the king that was baseball.

Once bitter rivals, the American and National Leagues partnered in the early 1900s to form the modern incarnation of organized baseball.

Hosting a professional baseball club had long reflected a city’s status within the national hierarchy, but to put perceptions bluntly: “minor” cities hosted the minor leagues while the “big” cities had the big leagues. The two playing under the banner of Major League Baseball.

Historically, it wasn’t necessarily unheard of for either an American League or National League club to discuss possible relocation or even undergo a move to a new city, but expansion via the introduction of new teams was far less common. Things rapidly changed, however, when two of New York City’s three baseball clubs jumped to the West Coast in 1958.

Location of Major League Baseball’s clubs in 1957 prior to the first West Coast relocations. National League represented in red, American League in blue.

The political and professional intrigue surrounding the relocation of the Brooklyn Dodgers to Los Angeles and New York Giants to San Francisco is a story all its own, but what’s most important to our subject here is the fallout from that move. Before those teams moved across the country to California, only one of MLB’s 16 teams was located west of the nation’s metaphorical and geographic dividing line—the Mississippi River (and just over the line at that). Then begrudgingly calling Kansas City home, the Athletics saw potential. So did a number of growing cities in the middle, south, and west of the country who had long been vying for major league franchises of their own. The exodus of the Giants and Dodgers made it official: the manifest destiny of professional sports had arrived. There was room to grow and money to be made.

Location of Major League Baseball clubs in 1968 (the year the Athletics moved to Oakland). Following multiple instances of relocation and expansion, MLB now sat at 20 teams. National League represented in red, American League in blue.

In the decades that followed, dramatic stories of new teams, new rules, renegade leagues, and legal maneuvering would follow every established American sport. Political and business leaders quickly developed strategies for luring teams by any means necessary. Often, this resulted in the then-relatively novel concept of the taxpayers footing the bill for new, state-of-the-art stadia. Structures built in hopes of enticing an existing team to relocate or a league to expand. Team owners and league officials found themselves in an incredibly advantageous position. They could threaten their current markets with the possibility of relocation while dangling the same prospect before numerous, potentially new homes. It was simply a matter of who could offer them the best deal. Corporate welfare, after all, is perhaps the only thing more American than baseball itself.

Early models of the Oakland–Alameda County Coliseum [right] and Oakland Arena [left].”

[Oakland Tribune, 1963. Public Domain]

As the 1950s came to a close, officials in Oakland had come up with a fairly sensible financial structure while drawing up plans for the construction of a publicly-owned, multi-use sports complex. Featuring a large, outdoor stadium for both baseball and football, the campus would also boast an indoor arena that could accommodate basketball and ice hockey. All Oakland would have to do was sit back and wait, ready to welcome any of the nation’s top sports leagues.

The city had, technically, already received its first “big” team in 1960, but the Oakland Raiders had been a surprise expansion club in the fledgling American Football League—an organization that was solidly in second place behind the more established National Football League. It was assumed that the Raiders would eventually move to the Coliseum, but the new building was clearly designed to prioritize the then much more popular game of baseball. Taking inspiration from the well received and successful Dodger Stadium of Los Angeles, the Oakland-Alameda Coliseum debuted with a panoramic outfield view of the surrounding landscape.

The Oakland Coliseum’s original layout as seen in a 1984 trading card.

[Public Domain]

Oakland had been on the radar of several baseball owners and expansion groups ever since the Coliseum’s construction was announced, but even after the Raiders moved in and the stadium opened for 1966, no baseball commitment had been made. Still, the pro sports scene in Oakland continued to bloom as the NHL’s new Golden Seals began playing hockey at the arena next door in 1967.

And then, finally in 1968, Major League Baseball arrived.

The Oakland Coliseum’s original outfield configuration as seen in 1981.

[Nathan Hughes Hamilton/Wikimedia Commons]

Established in 1901, the Philadelphia Athletics had been a charter club of the American League. Crosstown rivals of the National League’s Phillies, the Athletics would become known for dynastic reigns that racked up multiple league pennants and five World Series titles. The team’s fortunes would soon trend downward, however, as they became hampered with ownership struggles, an aging stadium, poor on-field results, dwindling attendance, and the rising popularity of the Phillies. Facing economic insolvency, the team’s family ownership decided to sell the club with league officials being open to relocation. The Athletics would then find themselves departing the “City of Brotherly Love” for Kansas City in 1955, becoming baseball’s then westernmost team.

A young Tommy Lasorda with the (then) Kansas City Athletics in 1956. Lasorda would go on to have a notable managerial career that delivered him to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1997.

[Public Domain]

Arnold Johnson, the new owner and man responsible for the move, would die suddenly in 1960. The team then came under the ownership of businessman Charlie Finley who’d long sought to enter the world of professional baseball. Known for his outlandish marketing tactics and eclectic management style (as well as regularly drawing the ire of fellow owners and league officials), Finley quickly grew disenchanted with Kansas City’s aging Municipal Stadium. Although early plans were in the works for a potential, modern replacement, Finely already had his eye on Oakland’s new Coliseum. After just thirteen seasons in the “Paris of the Plains” (with none of them featuring a finish better than sixth place), the Athletics were on the move again for 1968.

Once basketball’s Warriors were lured from nearby San Francisco in 1971, the East Bay was afforded the unique distinction of hosting a team in the top league of each major American sport: The Athletics of Major League Baseball, the Raiders of the National Football League (who’d merged in with the rest of the AFL), the Seals of the National Hockey League, and the Golden State Warriors of the National Basketball Association. All of them residing within the Oakland-Alameda Sports Complex—a feat achieved in just over a decade of time.

The Golden Seals left in 1978, though—bound for a short-lived life in Cleveland—and while the Warriors were staying put for the moment, both the Athletics and Raiders were already eyeing potential moves by the 1980s.

A vintage postcard showing the Coliseum (left) with one of its original football arrangements (before the baseball season ended, the gridiron would be rotated 45 degrees with no extra bleachers brought in).

Raiders owner Al Davis had grown unhappy with the Coliseum’s baseball-forward setup and his inability to get improvements constructed that not only better suited the game of football, but could also make him more money. Finley, on the other hand, had been entertaining offers from cities like Denver and Louisville after struggling to compete financially with his rival team owners. Once the Raiders moved to Los Angeles for the 1982 season, however, it became unlikely that stadium officials would let the Athletics out of their Coliseum lease. Thus, Finley sold the team to local owners who pledged to keep the A’s in Oakland for at least the remainder of their tenancy obligation.

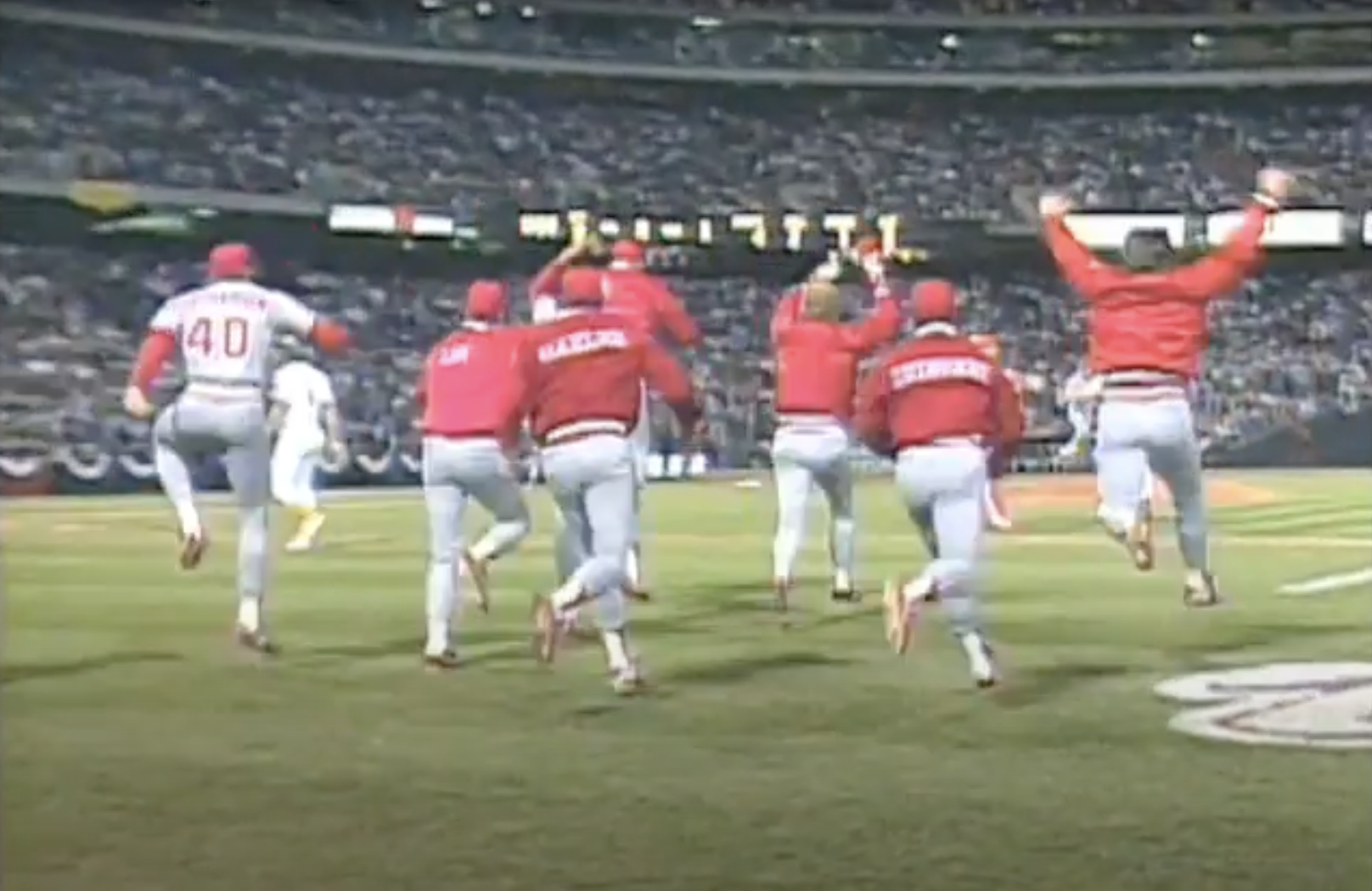

A fresh era of success then dawned on both the A’s and the Coliseum. After having delivered the people of Oakland three championships between 1972 and 1974, the Athletics clinched a fourth (and ninth overall) in 1989 while defeating their cross-Bay arch rivals, the San Francisco Giants. That year’s Series would feature names like Henderson, Eckersley, McGwire and Canseco, but it was also notable for becoming delayed after the Loma Prieta Earthquake struck during the third game. The A’s looked to repeat as Champions for 1990, but they’d be swept out of that World Series by the legendary “wire-to-wire” Cincinnati Reds.

The Cincinnati Reds celebrate their historic “wire-to-wire” World Series victory in the Oakland Coliseum on October 20, 1990.

[Screenshot from MLB Broadcast]

As the two teams still representing Oakland on the stage of major league sports, baseball’s Athletics and basketball’s Warriors had become deeply ingrained pieces of the East Bay’s identity by the 1990s. The Los Angeles Raiders agreed to rejoin them in exchange for publicly funded, football-forward upgrades at the Coliseum—thus, the stadium’s panoramic view was replaced with a towering structure of seats and luxury boxes for 1996. Dubbed “Mt. Davis” by the locals in reference to Raiders owner Al Davis, this ~$500 million renovation was quite literally a half-measure: 50% of a brand-new football stadium awkwardly shoved into the outfield of an older baseball stadium. A situation that fans quickly found to be less-than-ideal for both sports.

[1985 / Public Domain]

Above: The Coliseum’s original, panoramic outfield view.

Below: The Coliseum’s outfield view featuring “Mt. Davis.”

[2019 photograph by Liannadavis / Wikimedia Commons]

Mt. Davis had increased the Coliseum’s seating capacity and revenue opportunities, but every major American sports league was in the midst of upheaval as the new millennium dawned. In addition to fresh rounds of expansion, teams continued to regularly pit cities against each other while in search of subsidized facilities and larger handouts. A wave of brand-new stadia opened across the nation while the Oakland Coliseum became regularly derided as “falling behind.” Especially after it became the only major league, American stadium to still serve as a shared facility between the top two sports of football and baseball.

Unlike the other multi-use contemporaries such as Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers, St. Louis’ Busch II, and Cincinnati’s Riverfront (which had all come and gone by 2005), the Oakland Coliseum didn’t feature a simple conversion process. Instead, the Raiders’ return necessitated a complicated dance of cranes any time the stadium was switched between sports.

The conversion of the Coliseum between the games of football and baseball was a much more complex process compared to other venues of the era.

[GIF sampled from Oracle Arena’s video]

Despite the awkward setup, both teams would occasionally flirt with on-field success. Yet, while the Athletics’s “Moneyball” era would inspire a Brad Pitt-led film and the Raiders hiring of John Gruden turned some heads, both teams eventually settled into established reputations of mediocrity. By 2006, the Athletics had started placing decorative tarps over the upper decks of Mt. Davis. Occasionally, high profile games would draw large enough crowds to demand all of the stadium’s seating, but on average—most baseball teams (let alone the ever-struggling Athletics) didn’t require anywhere near 50,000 seats. Closing these often-empty sections was seen not only as a way to reduce operating costs, but also bring fans in closer for what would hopefully be perceived as a more exciting atmosphere. Facing their own struggles with winning and attendance, the Raiders adopted a similar strategy starting in 2013—often using tarps to try and hide the empty seats they couldn’t fill atop Mt. Davis.

The Atheltics’ World Series titles commemorated in tarp form.

[2010 photograph by BrokenSphere/Wikimedia Commons]

By this time, the speculation surrounding the futures of various teams had become an established theme among the headlines of every sport. While Oakland’s Raiders, Athletics, and Warriors were always finding themselves mentioned at the top of the relocation rumor lists, all three also explored plans that might keep them in the East Bay. An outcome that would serve to uphold Oakland’s recognition as a “major league” sports city.

The proposed ballpark at Howard Terminal, intended to boast many unique features such as a green roof, was just one of several ballpark proposals aimed at keeping the A’s in Oakland.

[Oakland Athletics/Bjarke Ingels Group]

The Warriors went first, though, opting for a new arena back across the Bay in downtown San Francisco. The Raiders then left for a second time—departing for a luxurious, tax-payer supported, domed facility in Las Vegas. When it was all said and done, only the Athletics remained. Their sign outside the Coliseum’s parking lot proudly proclaimed: “Rooted in Oakland since ‘68,” but that was merely a historical fact, not a statement of loyalty.

By 2021, the club was firmly under the control of John Fisher. The son of Gap Inc. founders, Fisher’s silver-spoon career in various Bay Area business ventures had allowed him to initially purchase a minority stake in the Athletics before he would eventually consolidate ownership solely under himself. As proposals for potential new ballparks in Oakland (and nearby San Jose) came and went, Fisher was eventually given permission from the league to consider relocation.

Renderings of the proposed Howard Terminal ballpark, a plan that was abandoned in 2023.

[Oakland Athletics/Bjarke Ingels Group]

Much like Oakland had, Las Vegas boasted several successful minor league teams while experiencing tremendous growth and expressing a desire to establish itself as a major league sports city. That official recognition came with the somewhat surprising, yet rather successful, expansion of the National Hockey League to the city in 2017. After the Golden Knights took the ice, Las Vegas instantly became rumored as a potential landing spot for teams from all of the other top professional leagues (especially after those leagues finally began embracing sports betting). The NFL’s Raiders arrived in 2020 as serious interest continued from the likes of Major League Baseball, Major League Soccer, and the National Basketball Association.

When another attempt to build the Athletics a new home in Oakland started to fall apart in 2022—it was clear that Fisher and Co. not only had their eyes set on Vegas, but had already aggressively begun the work. Meanwhile, fans in the East Bay had long been turned off by a club that regularly boasted a losing record while always claiming to have one foot out the door. The Coliseum and its supposed inadequacies had been an ongoing distraction for years, but that wasn’t stopping the club from competing on the field or investing in a valuable game day experience. Other teams had done far more with less. Still, fans fought for both the A’s and their city. Even going so far as to organize a “reverse boycott” in an effort to demonstrate that while they didn’t care for the owner, they still cared for the home team and the game of baseball.

October 2024 renderings of the Athletics’ planned Las Vegas ballpark.

[Athletics]

Despite the outcry, agreements were “finalized” in 2023 for a new Athletics’ ballpark in Las Vegas. The plan called for the team to ideally move in by the 2028 season even though the city’s minor league club (and top Athletics farm team), the AAA Las Vegas Aviators, had just received a brand-new stadium of their own in the “Sin City” suburbs. There was speculation that both clubs might share the facility until a new, climate-controlled Athletics stadium was built along the Vegas Strip, but the Athletics ultimately decided upon a temporary relocation to the California state capital of Sacramento. A city which was not only already home to the top farm team of their arch-rivals, the San Francisco Giants, but had also attempted to lure the Athletics before.

Sacramento’s Sutter Health Park as seen in 2023. The facility boasts ~14,000 seats and is primarily a home for AAA-level baseball.

[Quintin Soloviev/Wikimedia Commons]

In December 2024, it was reported by ESPN that progress in Las Vegas appears to be on track for a 2028 Opening Day. Should no complications arise, the Athletics plan to share Sacramento’s minor league Sutter Health Park with the AAA River Cats for only three seasons beginning in 2025 before arriving at their next destination.

. . .

The guys slinging beer on the sidewalk out front, the security guard, the first beer guy, the usher, the second beer guy, a nice man I met named Alejandro, the folks waiting for the train, the folks on the train, the firefighters at the coffee shop, the folks bellied up to the bar—everyone knew who to blame.

“Fisher.”

Sure, ownership is always the easy scapegoat in any situation such as this. No one ever recognizes that the poor rich guy at the top did his “very best” or that he too weeps for the “millions of dedicated and passionate A’s fans in Oakland and around the world.” You may not realize it in your rush to judgement, but John Fisher totally gets that “there is great disappointment, even bitterness,” directed at him. He’s just a normal everyman like you. But, oh, if only he had the ability to speak to “each one of you individually,” then you’d see. You’d all see! John Fisher is “genuinely sorry.”

Look, baseball is a business. All professional sports are. No one’s innocent, life isn’t fair, and we’re all going to keep tuning in no matter how often fans get screwed. John Fisher’s “apology letter,” however, set a new low for out-of-touch, false sincerity. A hollow, rambling tirade that came at a time when it probably would’ve been best to just say nothing at all. Even someone like me—a person unconnected to the A’s in any meaningful way—could smell the corporate bullshit across the country in Cincinnati. You don’t have to take my word for it, though. Larry Bell, Sports Director of the Bay Area’s ABC affiliate, said it best in an impassioned televised address to John Fisher:

“As for the statement about loyal A’s fans...seriously‽ John, We’ve been trying to interview you for years, but you always choose to remain invisible! Unless you’re begging politicians for public funding, and then: you’re out in front in Las Vegas.”

A sun-faded map in the Oakland Coliseum.

Two dollars.

No indication of “processing fees” or taxes.

Just $2.00 on the dot.

As I stood on the platform, I wondered if this kind of a promotion would bring out more fans. Then, as packed car after packed car whooshed by, I had my answer. Aside from a handful of Rays hats, every soul aboard wore green and gold. Most of it was official merchandise, but a few folks sported the now familiar, yet sadly futile, “sell the team” shirts as the train rumbled out of the tunnel to soar above the industrial landscape.

I followed the momentum of the crowd through the annoyingly complicated Coliseum station—down some stairs, through the lobby, and back up more stairs to the pedestrian bridge wrapped in suicide-prevention fencing. Arriving at the back of Mt. Davis, a surprisingly deep line had formed. Rather than stand around, I went to find a piece of history sitting in the parking lot: the seats they used to haul in via cranes for Raiders games.

It was almost time for the first pitch, so I meandered back to the stadium and found a line that was even longer than before. The promotion of $2.00 tickets and the promise of $1.00 hot dogs had attracted an agonizingly long line for an understaffed gate.

The line of fans waiting to enter the Oakland Coliseum on August 21, 2024.

I finally made it inside at the bottom of the fourth inning only to discover that if I wanted to take advantage of the evening’s dinner deal—I would need to find a concession booth that was not only open, but didn’t feature overwhelmed staff screaming: “We are out of hot dogs!”

Once I located a stand that checked all those boxes, I wasn’t willing to miss another half of the game just to wait in line for the privilege of being limited to only two questionable looking entrees that could best be described as “wet food logs on white bread.”

So, I settled for beer.

“This one’s on me, brother, have a good time,” the vendor said while passing me a freshly cracked Modelo.

We’d been chatting the night before and his kind gesture lifted my mood as I took a lap around the building and tried to decide how best to enjoy what little time I had left with the Coliseum.

An unattended bar in a lounge area of Mt. Davis features a sculpture of the Athletics’ elephant mascot, as well as, several layers of dust.

Another reminder of Riverfront: offices above the concourse. Note the cabling.

A “premium” seating area within the Coliseum.

The Athletics’ history hallway.

Once again in the upper deck, the stadium’s speaker system constantly screeched with feedback as some unseen soul at the volume controls kept trying to rein it in for an official attendance of 10,339. A crowd that, unlike last night’s, didn’t seem to care for the good-natured team videos on the jumbotrons or even the clips being played in honor of the Coliseum’s history.

The game itself also did little to illicit reaction, even as the Athletics pulled even with Tampa in the midst of a pitching duel.

With Seth Brown up to bat, the sun setting on the Oakland skyline in the distance, and “Tell Me When To Go” by the city’s very own E-40 shaking the mostly empty stands, I said: “fuck it,” embracing the attitude expressed by both the team ownership and the few remaining fans.

I made one last photograph, chugged my beer, zoned out, and simply watched baseball as the A’s failed to rally. A pleasant evening in a delightfully fascinating place that I was glad to have experienced before baseball left.

Headed for an airport-bound train the next morning, I walked through the fare gates beneath a banner that read: “Come celebrate Oakland all summer long with the Ballers at Raimondi Park.” A member of the independent Pioneer Baseball League, the Ballers were established by fans in response to the Athletics’ planned departure. The effort also lead to the renovation of a neglected ball field in West Oakland that can now accommodate 4,000 fans. Nicknamed “The B’s” and sporting similar colors to the MLB club that turned its back on the city, the team has found strong support in their inaugural season.

Oakland Ballers advertisement in the 12th St. Oakland City Center BART station.

As I stepped aboard the BART train and continued to read about the city’s new ball club, it was becoming clear that the momentum and enthusiasm behind the Ballers was a genuine, grassroots effort. A positive development that extended itself to the community in a way that the John Fishers and Al Davis’ of the world never could. An undertaking similar to that of the highly successful Oakland Roots Soccer Club—a team which will move into the Coliseum for 2025.

Promotional graphic showing the intended 2025 soccer field orientation at the Coliseum.

[Oakland Roots]

In the terminal, I thought about all of the Coliseum’s supposed inadequacies. Objectively, yes, they indicated that the place is a dump—but it’s the only “dump” left. The last of the working person’s stadiums, not some publicly funded palace glitzed up with cheap decorations that will necessitate “renovations” in a few years. The only facility left in Major League Baseball that accurately reflected the reality of the world outside its sterile, concrete walls. Sure, it lacked most of the charming, historic aesthetics found in places like Wrigley or Fenway—but Fenway is priced like a country club and Wrigley is now “Wrigleyville.” The Oakland Coliseum experience, on the other hand, had more in common with the common fan than any other cathedral of the sport. It was a fine place to drink a beer and watch baseball, one where the smells of cheap street food could still be found outside the gates. A place that was uniquely “Oakland” and a perfect, stark contrast to the San Francisco Giant’s (consistently top-ranked) Oracle Park across The Bay. With a few updates and a renewed focus on an affordable fan experience, the place could’ve easily served as a unique attraction unlike anything else in baseball—a sport that continues to struggle for relevance and one that has now sadly, yet not surprisingly, chosen to abandon what was affectionately called its “last dive bar.”

As I boarded the plane and read up on the latest plans for developing the Coliseum site, I made a note to check the Oakland Roots schedule next year. Baseball may be gone, but the “dive bar” isn’t dead just yet.

Since 2007, the content of this website (and its former life as Queen City Discovery) has been a huge labor of love.

If you’ve enjoyed stories like The Ghost Ship, abandoned amusement parks, the Cincinnati Subway, Fading Ads, or others over the years—might you consider showing some support for future projects?