Late in Life Skateboarding and The Legend of Rock-A-Hoola

The abandoned Lake Dolores Resort and Rock-A-Hoola Waterpark as seen in 2020.

Digital.

I was never good at skateboarding. Terrible, even. My portfolio of tricks was limited to clumsy ollies and short manuals performed in the driveway of a suburban Cincinnati home. Several years later, while leaving my first apartment to go move in with my girlfriend at the time, I came across my old board: a Black Label deck with blue Phantom trucks and neon green Spitfire wheels. A once prized possession originally ordered from the pages of CCS. Maybe I donated it, maybe I chucked it. Truthfully, I don’t remember its fate aside from my belief that it was time to truly embrace what I then believed was adulthood.

In short time, I regretted that, though. I missed the board even though I hadn’t really used it much as I had aged. Still, the idea of skateboarding ate at me. I’d think about the activity in the way I once had as a teenager. “It can’t be that hard. Not if you practice enough.” So, on an impulse, I snagged a new board off Craigslist years later at the age of 30. After some time spent rolling around Downtown Cincinnati on my lunch breaks, I’m still no good at riding it even at the age of almost 32. I didn’t want to tell anyone about it, but now I don’t care. I love and fully embrace my “late in life skateboarding” interest.

Even if I still can’t ollie. Even if I trip every time I come to a curb on a city block.

Surf Cincinnati, the first abandoned locale I ever documented, circa 2007.

Nostalgia can hold so much over a person. Despite having written about it, talked about it, and studied it for so long—I still find myself surprised at the power it has. I had never felt unfulfilled walking away from skateboarding as a teenager (walking away from a black belt in Tae-Kwon-Do, however, I truly came to regret). But when I discarded that original board, it left me with small pangs of heartache that reverberated until I picked up the pastime again. Maybe I saw my renewed interest as some sort of atonement, some recognition that I no longer needed to suppress certain thoughts, feelings, and interests. Perhaps the notion wasn’t all that deep, but acquiescing to the lure of the skateboarding was the first time I had felt any sort of true nostalgia for the period in life when I was 14, awkward, and falling down on cold concrete. A period of time that came right before a more notable personal era, one I’d actually grieve for and lament in the years to come: the days when I worked at an amusement park and made my first forays into urban exploration, photography, and writing. Often, those four things would overlap. I’d take a few days off from my job at an active park to explore and document an abandoned one. I tried to be conscious of how both worlds related to each other, but couldn’t articulate those themes until much later. Then one day, all of these subjects (and skateboarding) collided.

I’m not sure how I first came across it—but Brett Novak’s film, “Altered Route” starring Kilian Martin, shook me. The music fit perfectly, the visuals were beautiful, the skateboarding performance was mesmerizing, and the setting was just incredible: an abandoned water park in the middle of the Mojave Desert. It had everything: visual work, creative pursuits, history, storytelling, and nostalgic pastimes wrapped into one. Over the years, I’ve probably watched it hundreds of times. It wasn’t just a basic VHS skate film, it told a story—one that crossed scenes from the park’s past days with Martin gliding across the present, decrepit landscape. I listened to the featured Patrick Watson song all the time. I thought about skateboarding. I dreamt of visiting the abandoned park in hopes of adding it to my list of many others.

Just a few of the many abandoned amusement parks I’ve documented over the years.

In the same ways I had suppressed the urge to revisit skateboarding, though, I made excuses for not seeking out the park in Martin’s video. When would I have enough time and money to venture out into the desert on the other side of the country? Then one day: I was a person who had those answers, casually strolling through the graffiti covered former entrance in the desert heat.

Entrance.

Digital.

“Still fun for the whole family,” said Travis as he looked ahead. We weren’t the only ones exploring an abandoned waterpark in the middle of the desert this day. Aside from the dad with his pair of kids, there were a few more groups walking about. Not that this location was particularly hard to visit. The first abandoned park I had ever explored, Surf Cincinnati, required a pants-tearing climb over a fence. Rock-A-Hoola only needed a jaunt across a crumbling parking lot. We simply pulled up and parked in a line of other visiting cars before walking unimpeded through the entrance. This place was still a tourist destination even after its original life as one had ended.

Rock-A-Hoola’s former entryway fountain.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

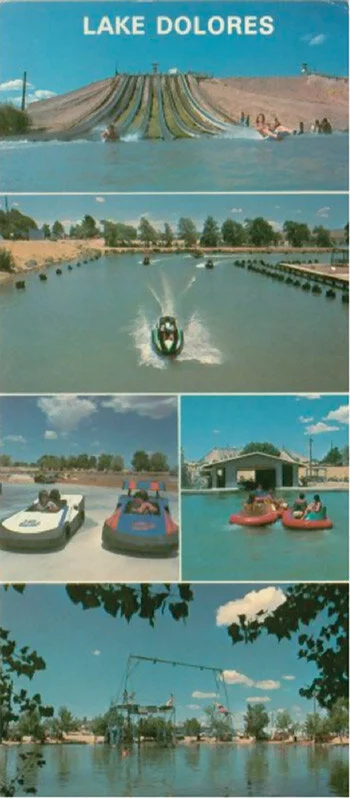

The Kilian Martin video highlights what was probably this park’s most prominent existence: a 1950s themed tourist destination that paired modern fiberglass water slides with doo-whop whistfulness in the late 90s. According to Eric Herman of Aqua Magazine, though, water attractions had originally debuted at the site in 1962. Lake Dolores, a man-made body of water named for the original owner’s wife, was fed by underground aquifers and the dirt removed for developing the swimming hole was used “to create a massive man made hill that towered over the otherwise dead-flat landscape.” The hill was adorned with several slides (primitive compared to the kind found at today’s parks) and early versions of “zip lines” that sent guests careening into the water below. Herman goes on to highlight the park’s most notable attraction, “the infamous Stand-Up slides,” with this anecdote:

“As the name suggests, they were waterslides you rode standing up. The slides consisted of wedge-shaped aluminum troughs with flat bottoms upon which you attempted to stand, descending upright on a thin stream of water. Riders reached terminal velocity before being shot off the end, at a height of 15 feet with a slight downward angle toward the water waiting below.”

While the years went on, Lake Dolores adapted to the evolving amusement park/fun center landscape by adding go-karts, bumper boats, an arcade, and other attractions. By all indications, this original incarnation of the park ceased to exist sometime in the 1980s.

Vintage Lake Dolores brochure.

Located halfway between Las Vegas and Los Angeles on Interstate 15, a group of investors attempted to redevelop the property in the 1990s—replacing all of the previous features with modern waterpark attractions akin to the parks seen today. The Lake Dolores Resort and Rock-A-Hoola Waterpark opened in 1998.

Commercial reel for the Lake Dolores Resort and Rock-A-Hoola Waterpark.

“Visitors are treated to an atmosphere filled with classic Americana and family fun,” states the narrator in the above promotional video for the park. Clips from the video were interspersed throughout the previously mentioned film, “Altered Route,” showcasing how the park once looked before cutting to shots of Martin skating through the same scenes in their abandoned state. In addition to highlighting “18 brand-new aqua attractions,” including the “world’s largest family raft ride,” the commercial goes on to tout plans for a “cyber ready” RV campground surrounding the lake, as well as, a full slate of special events including car shows, concerts, and “jammin’ jet ski competitions.” Future plans called for a hotel, golf course, amphitheater, and wave pool.

Despite the video’s closing claims that there would be “no shortage of smiles” and that the management team was bringing “the world’s first waterpark into the 21st century,” the optimism would be short-lived. Racked with debt and held liable for a 1999 accident that had resulted in the paralyzation of an employee, Rock-A-Hoola was bankrupt and closed by 2000. Another group of investors attempted to revitalize the property as Discovery Waterpark in 2002, but their effort ran out of steam by 2004.

In the ensuing years, several slides and attractions were sold to other parks while many of the Rock-A-Hoola’s mid-century inspired buildings and theme elements remained. Although various plans would get announced for the property, nothing substantial moved forward. In addition to 2012’s “Altered Route,” a 2008 episode of MTV’s “Rob & Big” also featured a skateboarding segment filmed at the park. Abandoned for years, the remaining structures became a canvas for artists. A 2018 fire turned two buildings to ash.

Overview of Rock-A-Hoola in 2020.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Back when Surf Cincinnati still existed, it hadn’t just been a casual creative subject. I had known the place when it was alive and even after it died, I kept coming back with my camera to explore the place over and over. I’d do this thing where I tried to imagine the ghosts of its past—compose a shot and look out at the landscape, trying to imagine what it had been like years ago with people roaming about. More often than not, I thought of the employees. Folks like me who had spent their summers slaving away at an amusement park. At Rock-A-Hoola, I surprisingly couldn’t conjure up the same visions or pangs of nostalgia for my past lives. All I could envision was Kilian Martin, molding and adapting the space, turning it into a canvas for his art, a place for him to skate. With all the graffiti (both artistic and civilian), debris, ruins, and dead palm fronds about—it was hard to focus in on details. But if I pictured Martin skating, I could see clearly. Rock-A-Hoola had become a legend in my mind thanks to him. And now I was there. So happy to be there. To have made it.

At that moment, I was present. For awhile—nostalgia, regret, and anxiety ceased to exist.

Digital.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Digital.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Digital.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Pentax K1000 with Kodak Portra 400.

Digital.

In the months since returning from this trip out west, I’ve still pursued “late in life skateboarding.” It hurts my left knee, I still can’t take curbs properly, and my arms flail like a bird when I try to ollie. But there’s a happiness in the activity, a centering of the mind. I love it. And I’m going to keep doing it if only in hopes of one day bringing my basic skateboard with me on a return trip to Rock-A-Hoola. In the meantime, this forgotten park has become another chapter in my reflections of life and nostalgia—a personal tale channeled through recollections of days spent in amusement parks both active and abandoned. I thought I had finished that story once, but there’s more to add and I think about it every time I’m on that board rolling around the city.

One day I may learn how to finally ollie and one day I may finish that memoir.

Addendum:

I don’t know what put me on the ground, I only remember how much it hurt. I tried to push up, but my left side gave out. As my right hand brought me to a standing position, my left throbbed and buckled with a kind of pain I had never felt before. I found my board in a patch of grass nearby. I wanted to slam it against the ground, but I didn’t have the strength.

After a night of icing my hand with a pack of frozen corn dogs, I cleaned off the dried blood above my eyes, on my chin, and on both of my battered knees. I was planning to get on my way, on the road towards my latest project, but several people convinced me that the emergency room was a better destination. The ER folks were kind, but apparently wrong. A specialist the next day derided their apparently sloppy diagnosis and prepped me for surgery. Less than 48 hours later, I was waking up to my left hand still attached, but out of action.

When I had crashed, I had actually been on my way home to publish this story. Now, I’m amending the ending—typing with my one still functional hand. In six or so weeks, the dislocated and broken carpals/metacarpals will have hopefully healed. I don’t think I’ll skate again, but I’ve re-read this post and my previous thoughts about “late in life skateboarding” several times. To a degree, those initial sentiments still stand. Maybe that opinion will change once the insurance bills roll in, but for now, I haven’t chucked my board like I did my last one. I’ll keep it, just on the off chance that I get to use it one last time. The only place I ever would, though: on a return to Rock-A-Hoola.

I don’t like to quote song lyrics in the stories I post here (or in the previous iteration of this site), but there’s a song by Goldfinger really sums up how I feel at this moment. The track, “Superman,” was popularized by the 1999 video game “Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater,” released when I was ten. At nearly 32, about to celebrate my birthday with a hand held together by pins and wires, it feels very fitting.

“So here I am,

Growing older all the time,

Looking older all the time,

Feeling younger in my mind

Here I am, doing everything I can

Holding on to what I am,

Pretending I'm a superman.”

Me, my dog, my cast, and the guitar I can’t play for eight weeks.

Portrait by Phil Armstrong.

The above story is Part 5 (of 7) in a series from a trip out west.