When a City Dared to Dream: How the 2012 Summer Olympics Could've Been in Cincinnati

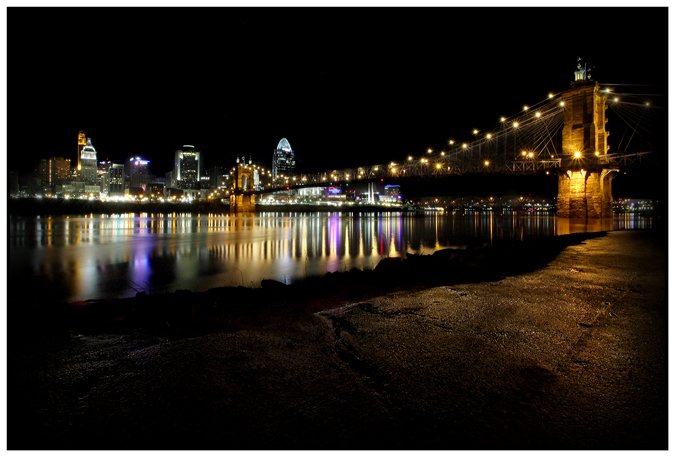

A London 2012 Olympic pin lies in the foreground while the skyline of Cincinnati, Ohio shines in the background. Had things panned out differently—it could’ve been the Queen City's skyline on that pin instead of London's.

Tomorrow the Games of the XXX Olympiad will officially open in London, Englad. This will be the UK capital's third time hosting the modern Olympic Games. Athletes, media and spectators from all across the globe will converge on the historic city, but many don't know that all of this could've happened in Cincinnati.

It seems odd comparing a Midwestern American city to one with the global stature of London, but there was once an official push to place Cincinnati on the world stage for this summer's games. While it may have been a long shot and was sometimes easily dismissed, the Queen City’s bid was real and did eventually help Cincinnati land a different marquee event.

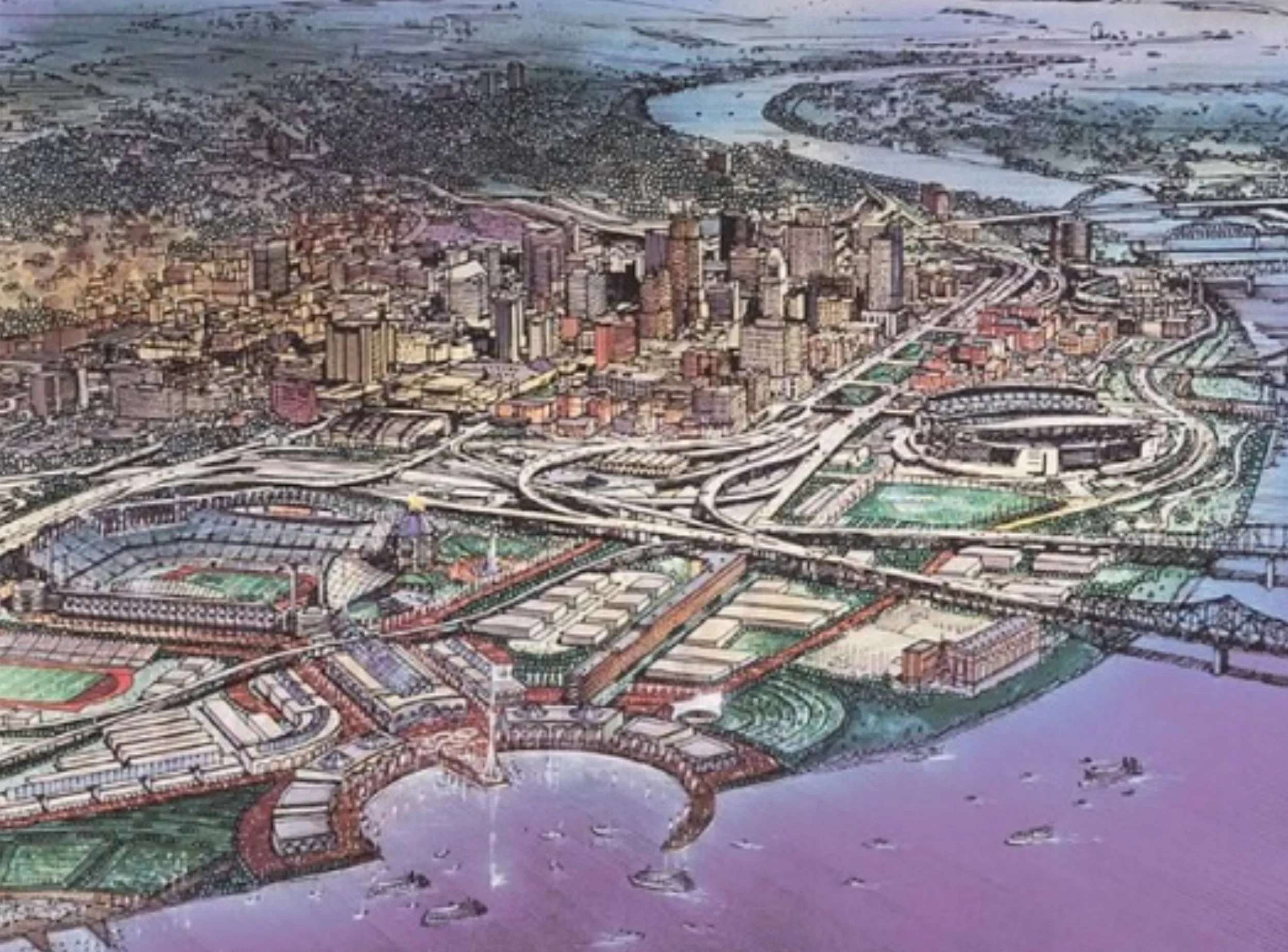

Artist rendering of a proposed Cincinnati Olympic Park.

The Cincinnati riverfront today hosts two world class sports venues: Paul Brown Stadium and Great American Ballpark. Imagine though, that just west of the stadia there's an 80,000 seat stadium proudly displaying the Olympic flame. In front of it: a harbor and Olympic park that runs right to the river from where Cincinnati was born. As the artist's rendering shows above, Cincinnati's riverfront would've been wildly transformed and it was only the tip of an iceberg that included the entire state of Ohio and even cities in Kentucky.

But the Olympics in Cincinnati—Really?

While the games are typically associated with much larger, more "international" cities such as London, Sydney, Los Angeles and Athens—once city broke down that perception in 1996 and it was Atlanta that got Nick Vehr thinking.

In a 1999 story by the Cincinnati Enquirer, former-City Councilmember Nick Vehr is seen working in his office where a statue of Don Quixote sits on his desk—an Olympic flag placed into its hands. It’s a reference to Veh’s reputation as a dreamer.

His political career culminated in 1996 after his final stint as a Republican on Cincinnati's City Council when he resigned to lead Cincinnati 2012—his non-profit organization devoted to brining the Olympics to Cincinnati.

“I think the single biggest challenge is convincing people it's OK to believe that it's possible. I sense that deep-down people want to believe this is doable."

- Nick Vehr to the Cincinnati Enquirer on March 27, 1999.

Vehr had given himself a lofty goal and set out to achieve it. Looking back, his enthusiasm and persistence show through in nearly every interview he gave with the papers, and even former political opponents praised his mission. Often indicative of Cincinnati, however, many scoffed at the idea and easily dismissed it, but Vehr was determined and continued to dream big. By the time the bid was due to the United States Olympic Committee (USOC), Cincinnati 2012 had raised $5.3 Million. Vehr's vision to make Cincinnati an Olympic host city was bold, but despite some shortcomings—the Queen City did boast several advantages.

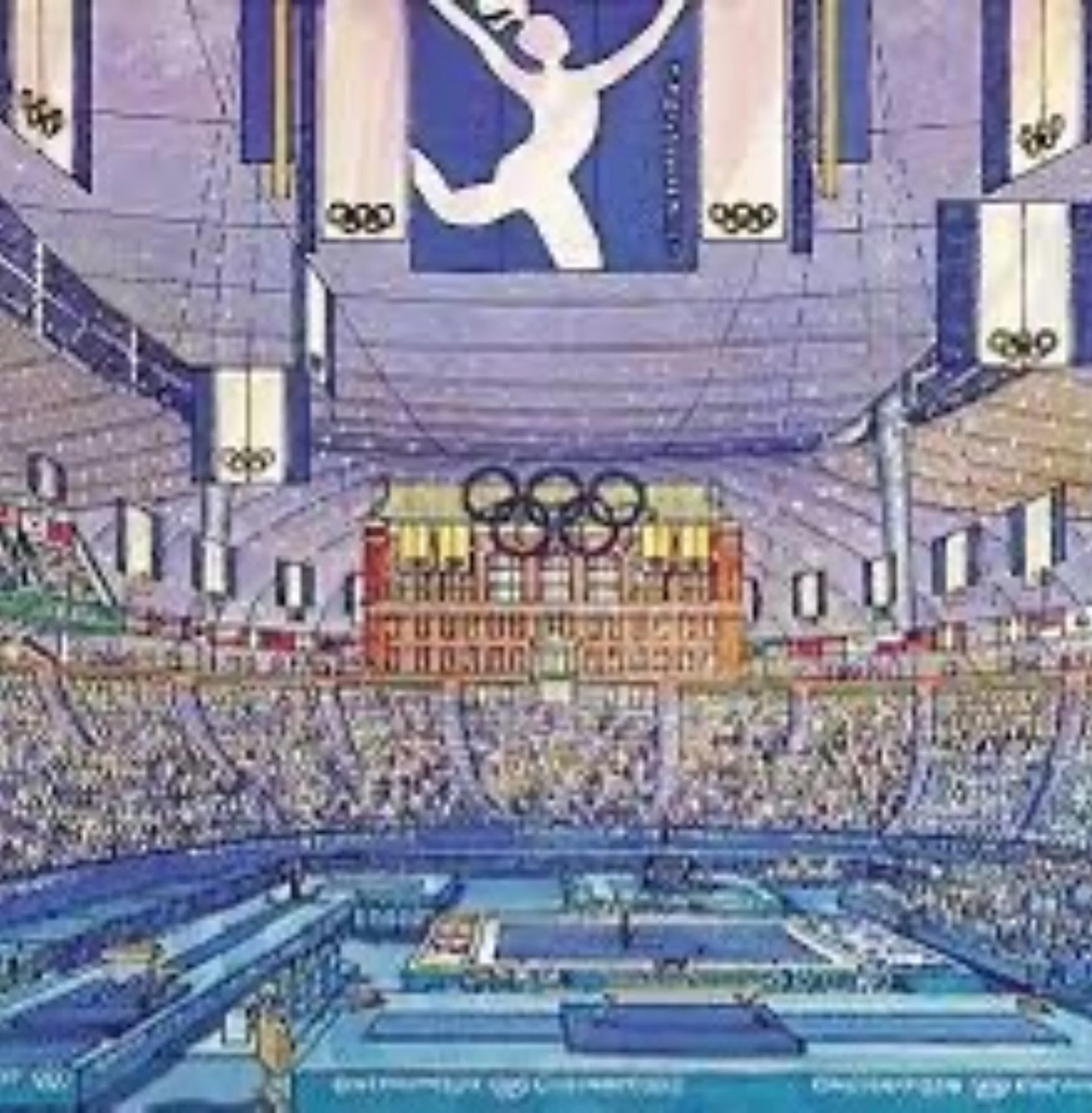

The plan for Cincinnati's olympic bid called for placing a dome over the University of Cincinnati's Nippert Stadium. While traditionally an American football field, it would've held various events including the medal rounds of basketball.

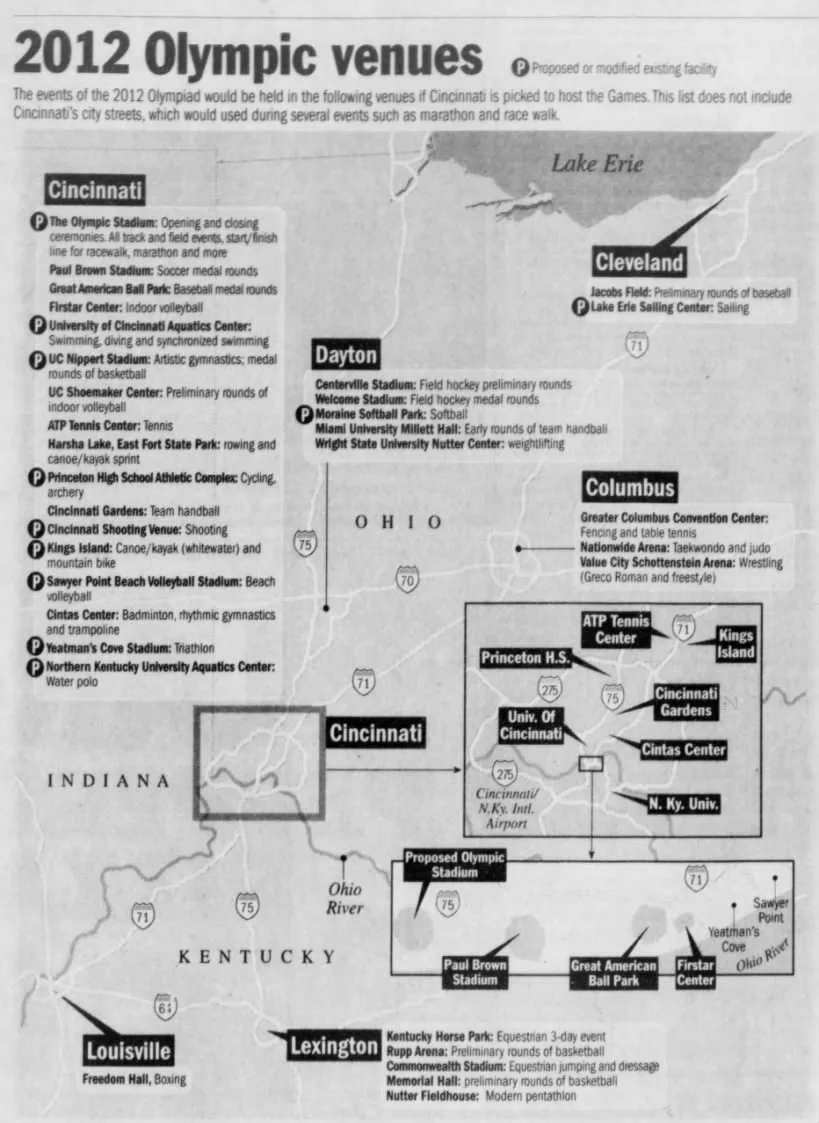

Before you can start thinking of Cincinnati as an Olympic host, however, you need to rethink how you define “Greater-Cincinnati.” The games wouldn't have taken place just with Queen City, but across the region. While the majority of the events would've been in the metro area; plans called for the use of Columbus' then brand new Nationwide and Value City Arena's, both of which sat over 18,000 spectators. Dayton would've seen events and even Cleveland would've been utilized for sailing on Lake Eerie and early rounds of baseball (which is no longer an Olympic sport). In nearby Kentucky—Lexington and Louisville would've been tapped for preliminary rounds of basketball, boxing, and equestrian events.

At the heart of it all would’ve been Cincinnati, though. A freshly-domed Nippert Stadium and several other venues on UC's campus would've been complemented by downtown’s US Bank Arena and both of the soon-to-be completed Paul Brown Stadium and Great American Ballpark. Xavier University’s Cintas Center, the historic Cincinnati Gardens, and even Northern Kentucky Unviersity would also be called upon. Sawyer Point would be transformed into a massive beach volleyball complex and Kings Island Amusement Park was mentioned as a potential event ground near the rapidly expanding ATP tennis stadium in Mason. While the downtown convention center would serve as a media hub, Cincinnati was missing a stadium large enough to be the main Olympic stadium. Plans called for a new 80,000 seat arena to be built west of Paul Brown Stadium in a proposed Olympic park. After the games, most of that seating would be removed and the stadium would be transformed into a 15,000 seat arena that could potentially host a future Major League Soccer franchise..

Utilizing an entire region to host the games was not an uncommon practice. Similar plans had taken place in Atlanta and would eventually be seen in Sydney on an Australian-wide scale. For their own respective 2012 bids—the combos of Orland & Tampa, Washington D.C. & Baltimore, and Dallas & Fort Worth were also floating regional plans. Cincinnati held an advantage, though, in that 70 percent of its venues would be in the greater Metropolitan area. Unfortunately, that was also a detriment to Cincinnati's bid. Because even with the majority of events centered around the city, how do you move the massive influx of people around?

Map of proposed and existing venues throughout the region that would've hosted Olympic events. Image credit: Cincinnati Enquirer/Newspapers.com

While the first phases of one are presently under construction, Cincinnati had no modern rail transit system at the time of Vehr's bid. Mass transit was limited simply to the area's bus system. Amtrak trains connected Cincinnati with Chicago, D.C. and New York, but interstate and intrastate travel would be limited to airports and highways. The lack of transportation options was certainly a hinderance to the Cincinnati bid’s plans, but a regional, light rail mass transit system was being pushed at the time. Had Cincinnati won the games, an influx of federal and state money would've certainly accelerated those plans (although, the transit plans were eventually defeated at the ballot box).

Other challenges facing Cincinnati's bid were concerns over enough hotel facilities, government funding support, and political issues. One of those potential hinderances was "Issue 3." Passed by voters in 1993, the amendment to the city's charter prohibited the city from extending legal protections to homosexuals. One of the amendments main pushers was local attorney Chris Finney. Perhaps best known for having his recent anti-passenger rail charter amendments defeated at the ballot box twice in the past four years, Finney penned the ballot language of Issue 3 and would later come out as a vocal opponent of the Olympic bid. Finney's group, the Coalition Opposed to Additional Spending and Taxes (COAST) would raise concerns over taxpayer risk to hosting the games. Even after Cincinnati submitted a formal bid, the outbreak of civil unrest in 2001 further caused critics to question the city's image in the face of international scrutiny.

Cincinnati Police lined up on Race St. during the 2001 civil unrest that followed the shooting of the unarmed Timothy Thomas. While waiting to hear back on its Olympic Bid status, many believed that what the media described as “riots” would negatively affect Cincinnati's chances. Image Credit: Ryan Thomas.

Despite the skepticism and criticism, Vehr held to his dream. On December 14, 2000, Cincinnati 2012 mailed their 806 page application to the USOC in Colorado Springs. Cincinnati joined the cities of Houston, D.C./Baltimore, Dallas, San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York City, and Tampa/Orlando in submitting bids. Out of the eight contestants, only one would eventually be selected as the USOC's recommendation to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) for the 2012 summer games. Even with the “riots” making international headlines that following Spring, Vehr believed Cincinnati still had a fighting chance.

“If we ignore it [the riots] and act as if nothing happened in April, then shame on us and we don't deserve to be a city going after the Olympics, but if we look at it as a historic moment in our city and work to ensure it never happens again — a path I believe we're on — then it could be helpful because it will show we care about all of our people.”

- Nick Vehr in an interview with the Cincinnati Enquirer on May 31, 2001.

The USOC paid a visit to the region to evaluate Cincinnati in the Summer of 2001. After four days of touring the area, the USOC's visit ended in an event hosted by Ohio Governor Bob Taft. Charlie Moore, chairman of the USOC's 2012 task force spoke highly of Cincinnati. He praised the fiscal plan for the games, how Cincinnati was dealing with fallout from civil unrest, its ambitious plan of "The Banks" neighborhood, corporate sponsorship, and the proposed theme of "Cincinnati: America At its Best."

“We wouldn’t be here if we didn’t think this was a legitimate bid. We respect it and are impressed by it. We've got a wonderful feeling about the commitment to host the Olympics here."

- Charlie Moore. United States Olympic Committee 2012 Task Force Chairman. Source.

Despite Moore's high praise to the press, there were still major concerns about Cincinnati—two of them being a lack of definite plans for funding an Olympic stadium and the lack of a sufficient mass-transit plan.

Proctor and Gamble's twin tower headquarters in downtown Cincinnati, Ohio decorated with branding from their 2012 olympic marketing campaign. For the 2012 summer games, P&G has sponsored 150 athletes across the world and embarked on a worldwide Olympic marketing campaign. 7/26/12 Image by Ronny Salerno.

Three months later on October 26, 2001, the USOC made an announcement narrowing down the cities it would be considering.

Cincinnati would not be one of them.

Of the eight applicants, Cincinnati would join Dallas/Fort Worth, Los Angeles, and Tampa/Orlando as the first four eliminated. Houston, New York, San Francisco, and D.C./Baltimore would all go on to the USOC's final contention. Eventually, New York City became the USOC's choice for international bidding, only to eventually lose out to London.

Nick Vehr's Olympic dreams had ended and Cincinnati 2012 closed up shop.

These days, it seems the only effort to attract the Olympics to Cincinnati in the future is a lonely facebook page advocating for the games in 2024.

Despite Cincinnati's elimination, Nick Vehr still helped elevate Cincinnati to the international stage.

In May 2009, Cincinnati was selected as the first American city to host the World Choir Games. Held every two years since 2000, Cincinnati would be hosting the 2012 games and had beat out St. Louis, MO and Reno, NV as competing bidders. Nick Vehr (who had since returned to working in public relations) and his company Vehr Communications were instrumental in bringing the Choir Games to the city. Vehr was named Managing Director of the event.

While relatively unheard of in the city before its opening, the World Choir Games brought over 15,000 participants from over 60 countries to the city. Cincinnati received press and attention both in the domestic media and abroad. Events quickly sold out, visitors crowded downtown streets and free "friendship concerts" were held all over the city in support of the games. Following the conclusion of the games, Vehr told WCPO:

"The people of Cincinnati smiled. They were friendly. They were helpful. They were proud that the world came to see us and I think they extended a hospitality that was over the top."

After Cincinnati was denied by the USOC, the city's Olympic bid began to fall back as a footnote of history and somewhat of an urban legend. Recently, while watching the Reds play the Cardinals on ESPN's national broadcast of Sunday Night Baseball, one of the commentators mentioned that Cincinnati "used" to be a great baseball city and "used" to have a great opening day parade (I guess he missed the massive parade we had this year and have had every year since the early 1900's). This city is often overlooked and under appreciated, even by those that live here. Nick Vehr dared to challenge the public perception of Cincinnati. He dared to dream big.

Cincinnati 2012 may not have brought us the Olympics, but it did bring a sense of civic pride to the city. Even as a ten year old, the idea of the Olympic Games coming here of all places was an unbelievable proposition—so unbelievable that I decided to research what happened and share what I learned.

I believe Vehr's story is worth telling and that dreaming of better things for this city is something that should never be forgotten. While in recent time, Cincinnati has certainly been on the rise, Vehr's Olympic story show us that you can combat the naysayers and change the perception, because Cincinnati is most definitely a city worth fighting for.

Cincinnati, a city of international caliber.

Further reading:

"Revisiting Cincinnati Stadia", Cincinnati Revisited, December 4, 2011.

"City Submits Olympic Bid.", Cincinnati Enquirer, December 14, 2000.

"Olympics Here A Long Shot.", Cincinnati Enquirer, December 10, 2000.

"Olympic Bid Due on Friday.", Cincinnati Enquirer, May 31, 2001.

Since 2007, the content of this website (and its former life as Queen City Discovery) has been a huge labor of love.

If you’ve enjoyed stories like The Ghost Ship, abandoned amusement parks, the Cincinnati Subway, Fading Ads, or others over the years—might you consider showing some support for future projects?