The Alignment of Cincinnati and Covington

If you were blissfully unaware of Midwestern georgraphy, you might look across at Covington from Cincinnati and assume it's all one big city, an urban street grid not separated by a river and state borders. That's now how it is, but here's the story of how Covington and Cincinnati physically aligned and continue to do so, with old ways of thinking still found today.

A few years ago, my friend Jake and I were contracted to photograph an event at the Northern Kentucky Convention Center. On our lunch break, we set off to wander Covington's fast food options near the highway, but he pointed out something interesting before we meandered to the dollar menu district: looking across the Ohio River towards Cincinnati, Covington's Madison Ave. lined up perfectly with Cincy's Race St. If you didn't know any better, the alignment made it seem as if the two cities were one. Looking in the direction of Ohio and the direction of Kentukcy, the respective streets maintain a clear direction towards the horizon. They appear like the long streets of Chicago, the kind of right-of-way that would have a subway system running beneath it and sidewalks dotted with multiple entrances to the underground.

However, these are two different cities in two different states and there's no passenger rail running beneath the river connecting them. While both are integral to the greater metropolitan area, each side of the river does have a distinct feel and culture. In the last few decades, many have seen them as competitors, a prime example being that we were at Northern Kentucky's convention center that day rather than Cincinnati's. Businesses and developments occasionally angle for government incentives, playing both shores against one another and the recent discussion of a soccer stadium has ignited an often heated debate over what exactly counts as "Cincinnati."

Nevertheless, the two areas often work together, as seen with the joint bid to try and lure Amazon's second headquarters. There's people on both sides of the Ohio who claim they'll never cross, but the reality is most people don't care too much about the border (over the years, I've lived on both sides of it). Northern Kentucky has several cities lining the shore across from Cincinnati, the largest of which is Covington. The story goes that when Covington was planned, the initial streets were aligned with Cincinnati's, symbolically linking the two population centers and looking ahead to when bridge technology would evolve to link them. Five of the original thoroughfares were named after Kentucky's first five governors: Shelby, Garrard, Greenup, Scott, and Madison. I'm not sure whether it existed with the original 1814-1815 plans, but according to an Atlas on file with the Kenton County Library, Kennedy St. was in existence by 1877 (although not named for a former Governor).

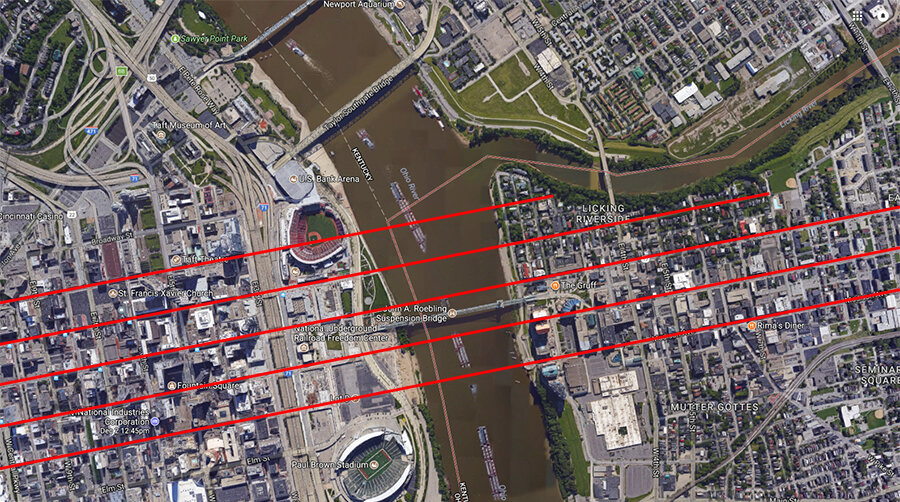

While Covington's Shelby St. does sit across from Cincinnati's Broadway St., it doglegs to the southwest, not following the direct lines of the other cross-state roadways. The alignment effect is most noticeable with Kennedy/Sycamore, Garrard/Main, Greenup /Walnut, Scott/Vine, and Madison/Race in Covington and Cincinnati respectively. Although the march of time has brought new developments and buildings, the views are relatively well preserved and as a whole, offer a glimpse into the minds of Covington's founders. Individually, each alignment tells its own story with unique views and sights.

Sycamore St. (Cincinnati) and Kennedy St. (Covington):

Looking South towards Kentucky from Cincinnati's Sycamore St., you won't see Covington's Kennedy St. Sycamore ends near Great American Ballpark, the home of the Reds which also obstructs the view. The ballpark features a reference to the Cincinnati street grid, though. The stadium's two upper decks are stylized after the baseball organization's previous two homes. Along third base, the stands are somewhat similar to Crosley Field, while the first base stands are vaguely mirrored after Riverfront Stadium/Cinergy Field. The physical space separating them is known as "The Gap" and it's the architectural feature from which Reds' mascot "Gapper" derives his name. The 35 ft. chasm aligns with Sycamore St. and consequently, Kennedy St. Envisioned as a way for passersby on the street to "see in, see the ballpark and catch a glimpse of the river," the stadium's walkways spanning the gap don't actually allow anyone on the street level to glimpse inside. Nevertheless, it does provide a unique vantage point for those attending a game.

Looking over from Covington, the ballpark does block any direct view of Sycamore St., but The Gap's alignment with nearby towers gives a physical acknowledgement.

Main St. (Cincinnati) and Garrard St. (Covington):

Cincinnati's Main St. flows downhill towards the riverfront, eventually ending at Smale Park where a pedestrian path, series of fountains, and set of steps continues the alignment. From the Kentucky side, these park features allow a direct view up into neighboring city.

Main St. becomes Joe Nuxhall Way below 2nd. St. where it borders the ballpark.

Walnut St. (Cincinnati) and Greenup St. (Covington):

Like the Main/Garrard combo a block over, Cincinnati's riverfront park features continue the street alignment here and presents a clear view when looking from Kentucky.

Greenup St. is known as Riverside Pl. above 2nd. St. in Covington.

Vine St. (Cincinnati) and Scott St. (Covington):

At Vine St., the Covington horizon looks a lot different than the blocks that precede Scott St. to the east. Here, Covington's skyline rises a bit higher and the view of the street alignment is obscured by a flood wall and buildings.

On the Kentucky side, it's still possible to look up into Cincinnati, but the view is only available via a walking path outside of the flood wall. The path also provides an excellent view of the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, which symbolically sits at the Ohio shore, once a point of freedom for slaves fleeing Kentucky and The South.

Vine St. becomes Rosa Parks St. below 2nd St. where it borders the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati.

Race St. (Cincinnati) and Madison Ave. (Covington):

This street combination is the one mentioned at the beginning of the article. Looking from the Cincinnati side, the long expanse of Covington's Madison Ave. is clearly visible and the buildings on both sides of the river help promote the illusion of a continuous grid.

From the Kentucky side, it's a little different. Cincinnati is framed by the flood walls and so long as the river isn't too high, you can step out onto the observation platform which used to be the Covington Landing's entrance. The view into Cincinnati is partially obscured. At the time of this writing, the riverfront development known as "The Banks" on the Ohio side isn't fully built out yet, currently sporting the supports of what will eventually be a parking garage beneath new buildings. The riverfront park is already extended to here, though. Like the streets seen before, the green space has features and steps which align with Race St. and Madison Ave.

It's interesting to think how each area would feel if they weren't separated by a state border and part of one continuous urban grid. Would Cincinnati "feel" bigger in a geographic sense rather than the visual one seen in clever angles? Would Covington be another Cincinnati neighborhood or remain independent even if it was flying the Ohio flag? It's not hard to envision how subway lines could run under these street grids like in other locales and to the same point, it's not hard to imagine bridges spanning each intentionally aligned thoroughfare.

|

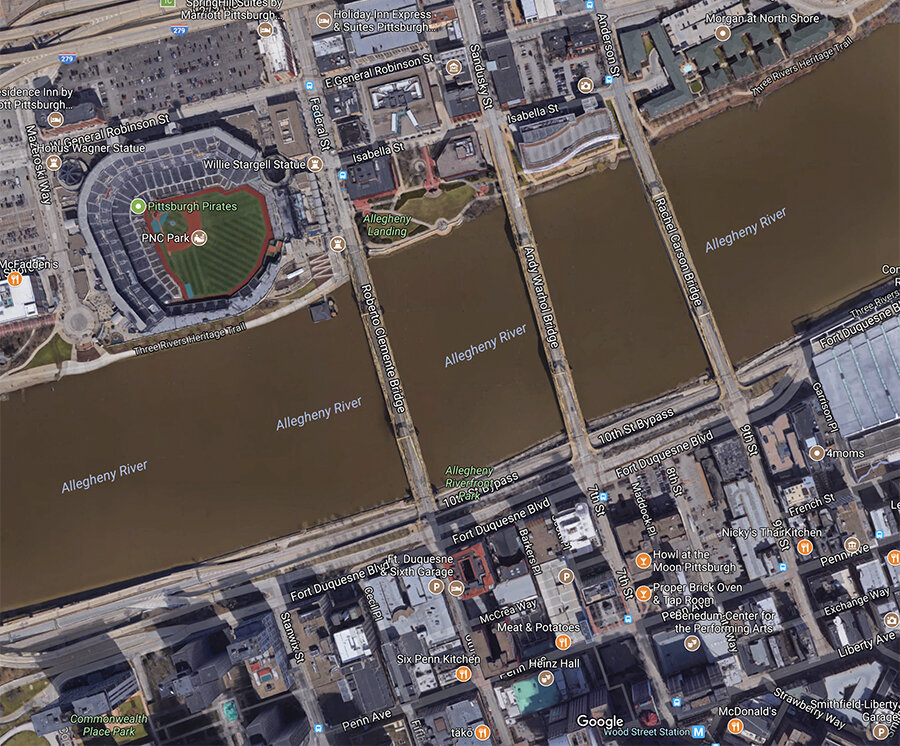

| - Bridges maintaining the street grid between Pittsburgh's downtown and North Shore neighborhood. |

As seen above, Pittsburgh's Clemente, Warhol, and Carson Bridges all span the Allegheny River in successive blocks, maintaining the street grid. Of the twelve roadways that perfectly align in six places between Cincinnati and Covington, though, none of them are linked by a bridge. While there are several river crossings today between Ohio and Northern Kentucky, the only one near the aligned streets is the first crossing, the iconic Roebling Suspension Bridge. However, it sits directly in the middle of Scott/Greenup in Kentucky and Vine/Walnut in Cincinnati.

|

| - Map showing how the Roebling Bridge sits askew of both the Covington and Cincinnati street grids. |

This was apparently a point of annoyance with the bridge's namesake designer John Roebling who later went on to design the Brooklyn Bridge. The offset span was due to ferry operators, who feared their businesses would suffer as a result of this technological innovation, purchasing land on both shores shortly after the bridge's construction was authorized. Anne Delano Steinart of the University of Cincinnati cites the locating of the bridge as:

"an example of the battle between an old technology (ferries) and a new one (suspension bridge construction)."

This all came in the wake of prior opposition to any permanent crossing between Ohio and Kentucky. Some Ohioans felt Covington would syphon off Cincinnati's economic vitality, while some Kentuckians worried the bridge would too easily facilitate the escape of runaway slaves. Well before the Greater-Cincinnati area argued over modern streetcars, voted down a regional light rail plan, dragged its feet on a proper airport, and abandoned its subway construction, we were battling the mythical ills of suspension bridges. This was all freshly in the wake of doubling down on riverboats as opposed to railroads, allowing the region to be surpassed in population by cities such as Chicago and St. Louis.

Nevertheless, the Roebling Bridge proved to be a mutually beneficial boon for both sides of the river. Today, it's an iconic source of pride for both cities. Over the past 25 years, its approaches have even been properly integrated into the street grids of Covington and Cincinnati via development projects. Much like the aligned streets, it's a physical symbol of how not just Covington and Cincinnati are linked, but Northern Kentucky and Ohio as well. The shores may be under the purview of different legislatures, but the region should take a lesson from how these streets align visually. The future of each city is directly linked to the other, even if not always physically.