Jungle Jim's Monorail

The story of a suburban legend and its journey from one "jungle" to the next.

The Jungle Jim's Monorail approaching a station, October 2011.

I had my first job when I was fourteen years old, getting paid under-the-table by our neighbor to help paint the parking lines on freshly paved asphalt. It was hot, tough, and always interesting, but the task instilled a strong work ethic and helped fund adolescent priorities such as laser tag. My boss, Dan, was known all over for his craft. Every place we stopped to paint, he seemed to have a great rapport with the business owners or was running into someone he knew well. One of our more interesting jobs was slapping down fresh yellow paint at Jungle Jim’s International Market—the eclectic, massive, globally known tourist attraction/supermarket in my hometown of Fairfield, Ohio.

Growing up, I initially spent far more time visiting “Jungle’s” than Kings Island, the local amusement park and another popular Cincinnati-area tourist destination. Jungle’s was our occasional grocery store when the deals were right, KI a place I didn’t know existed until I was six. One day, my Dad was showing me how these two worlds were colliding: Jungle Jim’s had purchased Kings Island’s retired monorail.

I was amazed.

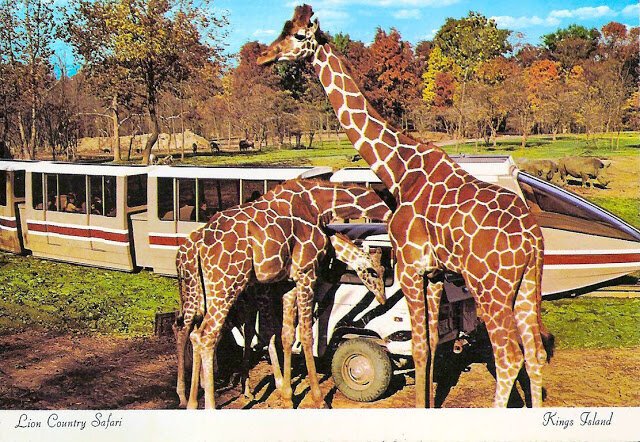

Kings Island's Lion Country Safari Monorail Postcard.

Image via KICentral.com

When I heard this news in 1998, nine-year-old me was blown away by the concept of this crazy, futuristic technology known as "monorail." I had no idea that Kings Island had ever possessed Disney-style transportation, let alone a system that traversed a full fledged zoo. I couldn’t believe that they’d close such an attraction, one I only knew from my dad’s casual recollections (he was nowhere near as impressed as me). These trains were now coming to our metaphorical backyard, to be installed at an already interesting shopping experience in the Cincinnati suburb of Fairfield.

“The monorail”—as it was casually known—became the subject of suburban legend. You could go around the back of "Jungle's" and see the cars lined up in storage. Eventually, the store installed one complete train on a piece of track near the main road. It was a showpiece, though, illuminated at night and occupied by the silhouettes of fake patrons. It felt like they were teasing everyone who had been curious. As the years went on, the static display was the only symbol of the monorail’s existence. Rumors would get passed around at backyard barbecues and the playgrounds of Catholic grade schools.

Was Jungle’s ever going to get the monorail running?

Was it too far gone?

Did they even still have it?

Then I got that job painting parking lines.

A monorail train sits in front of Jungle Jim's, 2008.

Jungle Jim’s was a regular client of my boss. Every summer, a fresh patch of the store’s parking lot would get re-paved. Dan and I would show up, lay down some chalk outlines, and fire up the paint machine. We took a break one evening when the man himself approached us.

James O. Bonaminio—the “Jim” in “Jungle Jim’s”—walked up to check in and catch up with Dan.

“This is my chance,” I thought. “I can get an answer about the monorail!”

I’ll admit, there were probably more important things in life that should’ve been weighing on my adolescent mind, but if this website has proven anything in the last ten+ years, it’s that a monorail mystery is a case worth taking on.

So I asked, straight up.

And I was blown away by the answer.

Train on the Jungle Jim's storage track, June 2008.

In the years leading up to asking this tough question, some supports had been installed around the store. It was pretty clear they were there to carry monorail track. A building had also been erected at the edge of the property. The supports led right up to what was no doubt going to be a station and maintenance building for the sleek, 70s era trains. But these various structures had existed for years and still, there was no monorail to ride. Now, I was getting the exclusive on what was coming.

The building at the edge of the property: that’d be the monorail’s main station and maintenance facility. The track was going to run from there, over the parking lot and to a second station situated above the store’s latest development: a collection of retail storefronts available for rent. From there, trains would circle the store and head towards the back, sloping down and into the main building. A third station would be located inside, within a new wine-centric section of the store. This station would be modeled to look like a European metro or subway stop. Like the “wine cellar” itself, all of it would be designed to give the illusion that you were underground. From there, the train would venture back outside and around to the main station, completing the loop.

Now, this was fifteen years ago. I’m not sure how accurate that memory is or if what I was being told was even a fully thought out, concrete plan (EDIT: While I’ve never gotten a firm confirmation on how far planned out this proposed track layout was, Phil Adams of Jungle Jims did tell us in the comments below that the store had looked at running the monorail over and across Ohio State Route 4 to property they owned across the street). Working in the amusement industry later in life, I’ve found that the most ambitious plans don’t always come to fruition. Back then, though, I was amazed. As a kid who hailed from the city with the abandoned subway, this was going to be huge (in my mind). Even if it was just an amusement ride and not actual mass transit. I anxiously awaited the construction of the monorail.

And waited.

And waited some more.

By 2008, I was studying Photojournalism, writing my first news stories, and had this website up for about a year. I had also left my asphalt painting job and been working in the Rides Department at Kings Island for a few seasons. What hadn’t I done in life?

Ridden the monorail at Jungle Jim’s.

Transfer track at Jungle Jim's, June 2008.

No one had. It still wasn’t open a decade after the saga began. Occasionally, someone would claim they saw it running along the small section of track that did manage to get built or that they had actually ridden it. You (or, at least, I) never believed them, though. When I came home from college for the summer, I drove by the store and saw two trains sitting in the station. They hadn’t just been assembled, but painted and cleaned up as well. The remaining trains were aligned on the transfer tracks, seemingly intact, but sporting their original livery—a faded and chipped tan base lined with a red stripe.

The Jungle Jim's fleet in storage, June 2008.

I wanted to know for sure this time. So I sent an email. Phil Adams, the store’s Director of Development, wrote back. He invited me to come out and see the monorail the next day. In the early summer of 2008, I found myself back at the store I had grown up going to. Phil toured me all around the monorail vehicles and their maintenance area while laying things out. Two trains and a small section of track were good to go, that was all they’d need. If there ever were any plans for a longer circuit that traversed the property and entered the store, that’d been scrapped. As it turns out, getting monorail track manufactured and sourcing parts for an amusement ride built by a long defunct company is incredibly expensive. The store is no stranger to displaying the absurd and eye catching (the massive facility is dotted with animatronics and unique attractions), but when groceries are your main business—even the more eclectic attractions can take a back seat on the priority list.

Monorail at the event center station, June 2008.

This was the new plan: Trains would be run from the maintenance facility (Station 1) to a station serving the store’s new event and banquet center (Station 2) above the leased out storefronts. The train would then disembark passengers, take on new ones, and reverse course back to Station 1 in a shuttle sequence.

Constructing the monorail had been expensive, but so was the operation. Instead of having the ride open daily to store guests, it would simply service happenings at the Oscar Event Center. To keep parking available for customers at the front of the store, event attendees would be encouraged to park at the monorail station and hop on a train to get to their gathering. In the case of a highly attended event, two trains could be pressed into operation.

A two-train operation would work like this: Train 1 could load up at Station 1 and then depart towards Station 2. Behind it, Train 2 would do the same. After disembarking passengers at Station 2, a now-empty Train 1 would pull forward to an extra section of track. Train 2 would pull up behind it, disembark its riders, take on new ones, and then reverse towards Station 1. Train 1 would then reverse into Station 2, take on riders, and head back behind Train 2. There was even talk of outfitting one of the trains with nicer seating (as opposed to the standard, molded plastic) and televisions that could display photographs of a recently married couple (if you were heading to a wedding reception) or a welcome message from a company (if you were heading to a business conference).

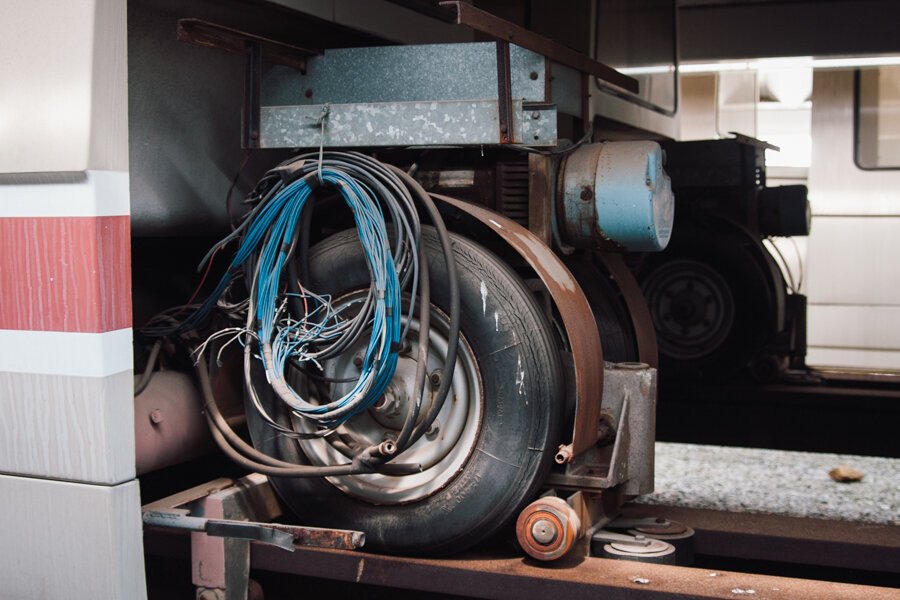

Monorail tires at the Jungle Jim's maintenance facility, 2008.

The trains had been modified from their days in service to Kings Island. The store planned to run seven cars coupled together as opposed to 9. The method of propulsion changed as well. Rather than use electricity sourced via the track, the last car of each train had its seating replaced by a diesel generator. Gas pumps were located at the maintenance facility and bio diesel would be the fuel of choice.

Bio diesel pumps, June 2008.

Then came Keith. I met him through the message board of KICentral.com, a Kings Island fan website run by some friends (you may remember them from the Americana/LeSourdsville Lake stories). Before he was a pastor raising a family out in Iowa, Keith had grown up in Cincinnati—and like myself—had once found employ with Kings Island. He had served as a monorail operator, the person who drove the trains through the park’s animal preserve. Often while piloting the vehicles, he gave spiels and provided riders with information about the wildlife and habitats they were passing through. He posted on the message boards often, sharing reflections about how much he had loved the job. After some online dialogue discussing the monorail’s history, Keith mentioned he’d be coming to Cincinnati to see some family. I worked out another tour of the “almost ready” monorail with Phil so that Keith could see it on his trip home.

Keith and Phil touring the monorail at Jungle Jim's, 2008.

With a big smile on his face, Keith gave me the best quote that day: “I feel like Captain Kirk returning to the bridge of the Enterprise!” he said while laughing and climbing into the driver’s seat of one of the old trains. He shared stories while running his hands over the controls, memories flooding back.

Monorail control panel, 2008.

We grabbed dinner afterwards and had this conversation that I enjoyed immensely in 2008, but didn’t come to truly appreciate until years later. Keith had all these great stories from working at an amusement park, a special fondness for a kind of time that had passed, but an experience I was then living in. Looking back on all of this years later, now long gone from the theme park world, I can relate to his words so much more.

As we said our goodbyes, “soon” was the word we were left with. As in: “soon” the monorail would be up and running.

Finally.

After all these years.

Sitting in storage for years, vegetation grows up around one of the trains at Jungle Jim's, 2008.

I’m not sure what “soon” ended up being. I was never invited to any weddings or business meetings at the event center. A co-worker of the time, who did use the facility for her wedding reception later that year, said the monorail was presented as an amenity, but was later told it wouldn’t be ready to operate in time. Maybe it did start running at some point in 2008? I don't know, I ended up going to back to college and eventually transferring to a school closer to Cincinnati, but moved away from Fairfield and over to Northern Kentucky. I wrote a story about Keith and the monorail for KICentral.com, but never gave the old ride much thought after that.

Trains in storage at Jungle Jim's, 2008.

Keith made another visit to Cincinnati years later, swinging by Kings Island to spend a day with his wife, kids, and family. I met up with him while I was working a shift, roaming the park and managing an area.

He asked me: “did you ever get to ride the monorail?”

By this point, it was 2011 and the answer was still: “nope.”

We caught up again later, enjoying dinner at one of the Jungle Jim’s restaurants that looked out at the monorail station from across the parking lot. Neither of us were terribly surprised that the ride still wasn’t running. As much as we would’ve loved to take a trip on board that day (or any day since 1998), we were both aware of how complex the project had been.

Monorail control panel, 2008.

Later that year, Jungle Jim’s was hosting its “Weekend of Fire,” an annual celebration of hot, spicy foods and their complements. They advertised that yes, believe it or not, they’d be running the monorail all weekend. Ryan: my roommate, friend, and one of the founders of KICentral.com who helped me publish my original story, headed up to Jungle’s with me on a Fall weekend. We parked out at the monorail station and joined a crowd of curious people, all of whom seemed to remark that they couldn’t believe this thing was actually running. A train pulled into the station, the doors opened, the previous guests departed, and we hopped on board.

The monorail approaches the main station, October 2011.

I’d been involved in opening some fairly big rides and attractions in my time at Kings Island, always excited to take that first ride when we installed something brand new and exciting. As cheesy as it sounds, I felt that same excitement, maybe even a bit more so, when I finally got on the monorail at Jungle Jim's. Nine-year-old me, who had never seen this ride at its original home, finally had his wish thirteen years later.

Inside one of the trains, October 2011.

It was slow, very slow. The diesel engine and its vibrations made the trains sound and feel like a more like a public bus. That’s not say it was uncomfortable, it was perfectly fine, but it wasn’t the same experience compared to gliding along the high speed tracks at the Disney parks. There was one section of track in the parking lot that I had always been curious about: an area that looked like it wasn’t exactly level, as if the points that came together on the support were a bit offset, slightly raised. Instead of the track running in a smooth horizontal line, it peaks slightly at this juncture. Sure enough, when we rode, the trains had to take this section even slower than usual and you could hear the bottoms of the trains run over the friction. Design flaw? Maybe, but even though it went slow, the train still cleared the section. It gained a little bit more speed as it pulled up to the event center and let everyone off to enjoy the festival.

A train awaiting riders at the store station, October 2011.

We walked around for a bit and sampled some foods, but let’s be honest: the monorail was the real reason we had come. So we got on again and enjoyed another slow crawl back to the main station. Overall, I’d say we enjoyed it. It was a cool experience, yet another incredibly unique attraction among the massive grocery store’s collection. It’s fitting that they own an amusement ride, the place walks a fine line between theme park and grocer. In terms of it being a tool to alleviate parking from the front of the store, well, it seemed to fall a bit short that day.

The fact of the matter is, the outer parking lot really isn’t that far from the main entrance. Even if the front lot is crowded and you have to park out by the monorail station, you can most likely walk faster. Ryan and I timed it that day, we made the walk from the station to the event center.

And back.

And back.

And back.

And back.

All before the monorail completed its route in one direction.

Nevertheless, if you’re attending an event there or have always been curious, it’s a cool thing to experience—an interesting piece of history to see revived. I’m so happy that the store saw it through.

A monorail conductor, October 2011.

I never rode the ride again after that day in 2011. I had heard it was open again on occasion for special events and festivals, but I never seemed to find myself up there when it was running. A second Jungle Jim’s location opened up on the other side of town, and while one of the monorail trains was used as a display piece above the entrance, it lacks a functioning train compared to the original location. In 2014, the legendary John Kiesewetter took a ride on the monorail with Jungle Jim. In that story, Jungle mentioned that future expansion of the train line could be possible and that for the time being, the ride was only servicing special events.

Trains in storage at Jungle Jim's, June 2008.

The photographs in this piece hail from the Summer of 2008 (when Keith and I visited) and the Fall of 2011 (when Ryan and I rode). I sat down to dig them up, re-do the photo editing, and prep them for this article in the summer of 2018, when I was still working in the public transportation industry. While discussing failed mass transit concepts of the past with a coworker, the subject of monorails came up. That’s when I unloaded on him the story of Kings Island’s monorail, its relocation to Jungle Jim’s, and my various adventures in the amusement and transit industries. Never taken seriously as effective public transportation outside of fairs, amusement parks, airports, and unique grocery store installations—monorail technology has somewhat faded.

I ended up swinging by Jungle’s in October 2018 and saw that the monorail’s two active trains had a new livery, that both vehicles were still situated to traverse the ~600 yards of track. A new maintenance building had been constructed to service the trains and several older vehicles still sitting on transfer tracks to the side. Via an email conversation with Jungle Jim’s, it was confirmed that the store’s original maintenance facility is being reconfigured into event space. Also: the monorail continues to only be used for special occasions and you can follow

their social media channels to see when it may be open.

*****

Update | Dec. 29, 2019: Over the course of 2019, Jungle Jim's original monorail station and storage track were fully converted into event space. A new train maintenance facility was constructed adjacent to the station/new event space. The station now features a bar that specializes in bourbon and facilities that can be customized to different events. As of this update, the bourbon bar is open two nights a week to the public, serving only special events at other times. The monorail itself does not run regularly, but can be utilized as an option when planning events. To see updated photographs and learn more information, check out this story I put together for Cincinnati Refined.

*****

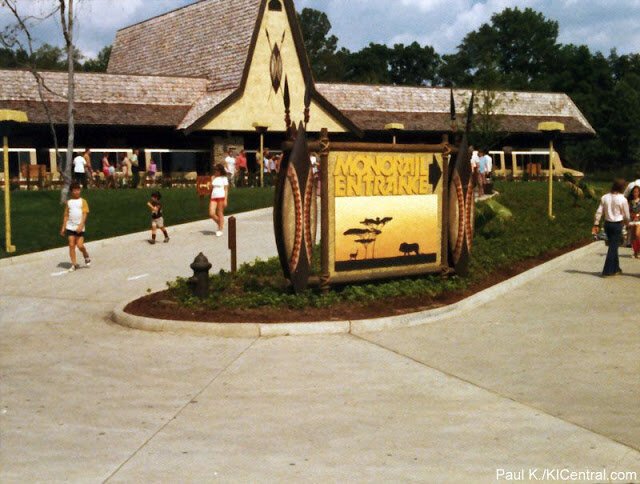

he monorail in operation at Kings Island in 1974.

Image via Paul K./KICentral.com

As I sat down to write this, I realized I never explained just how, exactly, the trains wound up at Jungle Jim’s. It was part of my original curiosity as a kid: why did Kings Island get rid of their monorail and close their zoo? Several other people have done all that research and shared that story before. Via KICentral.com, my friend Ty authored a history of the park’s defunct attraction and KI historian John Keeter also has a great piece on the park’s website. Both are wonderful, well written, detailed reads and I highly recommend checking them out.

I’ll offer a summary here with some information about the trains and their manufacturer as well (because, as I sit in an airport bar sipping beer, of course I want to write about monorail technology and former amusement park attractions rather than check my email).

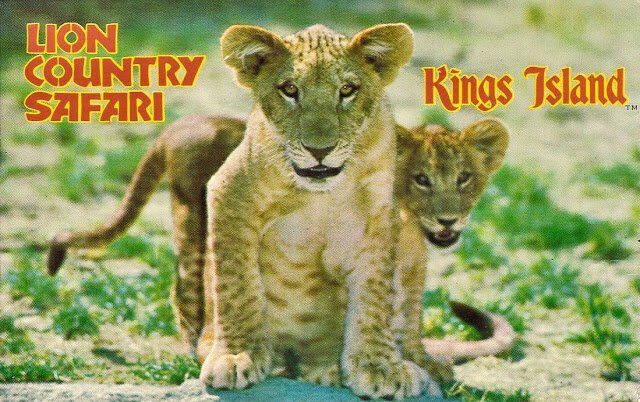

Kings Island opened in 1972. The iconic Cincinnati-area amusement park was born from the area’s historic Coney Island (and the logistical issues it faced). Landlocked near the river and prone to flooding, Coney’s owners worked with Taft Broadcasting to facilitate a relocation and new identity that would also birth something entirely new. Jumping in on the trends of the time, Kings Island debuted as a top quality, regional and seasonal amusement park that mimicked traits of the highly successful Disneyland and Walt Disney World destinations. In 1974, the park expanded with an entirely new area to celebrate its third season: Lion Country Safari. The “safari” area featured exhibits, gift shops, restaurants, and a newly built monorail that traversed a wildlife preserve spanning 100 acres. The $5.5 million investment was a truly massive expansion that featured a wide array of wildlife that included five giraffes, 70 lions, 25 rhinoceros, and 12 elephants among several other species.

Lion Country Safari postcard.

Image via KICentral.com.

The monorail itself featured track that ran for two miles. A popular trend for regional, seasonal parks of the era was to build these “safaris” as drive-through attractions where guests would pay an admission fee and pilot their own vehicles through the wildlife habitats. Accidents, vehicle damage, and logistics incentivized Kings Island to utilize a transportation system popularized by the Disney parks, technology often touted as the future of mass transit for major cities in the 60s and 70s.

Kings Island’s system was constructed by a company known as Universal Mobility. The “Tourister Type II” monorail made its first debut at an amusement park on the North Carolina/South Carolina border known as Carowinds in 1973 (Carowinds itself would eventually come to be owned by Kings Island’s Cincinnati-based Taft Broadcasting owners in 1974). Kings Island’s installation was the second incarnation of the system, followed by a third at its new sister park outside of Richmond—Kings Dominion—in 1975. Track was constructed low to the ground in order to give guests the best possible view of the animals (as opposed to well above ground at other amusement parks of the time).

A monorail traversing the Kings Island landscape in 1975.

Image via Johnny Fout/KICentral.com

Universal Mobility Incorporated had been designing and constructing monorails for parks at its Salt Lake City headquarters since 1967. I’m not entirely sure if their ultimate goal was to break into developing technology for mass transit (the vast amount of their installations were found at amusement parks or zoos). However, these projects were dubbed “minirail,” suggesting that the company had plans for larger versions that could accommodate commuters. A few other versions of UMI’s technology were eventually implemented at airports.

What's believed to be the Carowinds monorail as seen in a Universal Mobility Inc. document in 1983.

Image via AmusementParkIves.com

Perhaps somewhat ironic, Kings Island/Jungle Jim’s monorail wasn’t actually a “mono” track system. The trains, both then and now, actually use two rubber wheeled tires that run side by side, atop two “rails” that run in tandem. If you look from the side, the track appears as one rail, but if you look from above or below, there’s actually two segments of steel track placed in parallel proximity. More or less, though, the “Tourister II” looks and operates similar to the Disney monorails that brought the technology to the public’s attention.

Parallel monorail wheels and rails as seen undergoing work at Jungle Jim's, June 2008.

Kings Island’s safari wasn’t just an amusement park attraction, though, it was a full fledged functioning zoo that often worked in partnership with the iconic Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Gardens. Animals were bred, breakthroughs were made, and scientific research was performed. The Lion Country Safari would be expanded over the years with new animals, exhibits, shows, and even more rides. It was an immensely popular area of the park, despite the monorail ride being an up-charge rather than included in the park’s general admission costs.

In 1976, several baboons escaped and were the subject of multiple media reports until they were rounded up and eventually removed from the park’s lineup. A park ranger was killed later in the year, mauled by a lion and found dead by coworkers after he failed to respond to a radio call. By 1983, the monorail/safari attraction was renamed “Wild Animal Safari,” while the general park area became known as “Adventure Village.” Over the course of its life, the monorail station itself was host to various animal exhibits that kept waiting, train-bound guests entertained.

A Kings Island monorail operator in 1975.

Image via Paul K./KICentral.com

As Ty’s article points out in great detail, the partnership between Kings Island’s zoo and the Cincinnati Zoo can’t be understated. The amusement park wasn’t simply operating an attraction, rather, it was aiding in and advancing wildlife research despite the constant encroachment of new rides and attractions, as well as, the ever evolving landscape of regional amusement park operations encroaching on the safari’s borders .

A grazing giraffe as seen from within a monorail vehicle in June 1984. Note the track on the ground.

Image via Chris Albright/KICentral.com

By 1992, Taft Broadcasting had morphed and become the Kings Entertainment Company. Owning multiple seasonal amusement parks across the United States, but often regarded to have declined all of them in quality, the KECO team sought to sell their parks. Paramount Pictures, still a Gulf+Western Company and not yet under the Viacom corporate umbrella, wanted to develop theme parks in the vein of their Universal and Disney counterparts. Rather than build new properties from the ground up, they sought to re-purpose existing parks and drop in attractions themed to their films. Paramount Parks purchased most of the KECO properties by the end of the year. The acquisitions included Kings Island, Kings Dominion, Carowinds, Canada’s Wonderland, and the rights to operate Great America in Santa Clara, CA. (they declined a purchase of KECO’s Austarlia’s Wonderland in Sydney). Kings Island became Paramount’s Kings Island. An already planned roller coaster was quickly re-tooled and opened as “Top Gun,” themed to the movie studio’s 1986 hit motion picture, rather than something that fit in with the "Adventure Village" motif. In 1993: the monorail, animal habitat, Top Gun, and the movie studio co-existed. By 1994, though, the animals were all sold off and the monorails at both Kings Island and Kings Dominion were removed.

The Kings Island monorail as seen in 1974. From a 2012 QC/D story.

The trains sat idle on the park’s property until 1998 when Jungle Jim’s purchased all seven of them for $1 (plus fronting the cost of relocating the vehicles). Over the next several years, many of Kings Island’s new attractions would go on to occupy the land formerly used by the Wild Animal Habitat. Xtreme Skyflyer, Thunder Alley, Firehawk, Son of Beast, Banshee, and Flight of Fear have all occupied former grazing lands/monorail territory. Several old animal shelters and monorail structures were pressed into use for other resources. In the time I worked at the park, I often fetched wood coaster supplies from the “bolt barn,” a re-purposed animal keep modified to specifically house spare parts for the Son of Beast roller coaster. Another shelter at the far end of the park’s property was relegated to storage of what seemed to be completely forgotten mementos. You had to drive a pot hole-laden road past tall barbed wire fences (vestiges of the animal habitat) to reach a shack that held remnants of the defunct Hanna-Barbera Land. The monorail’s old maintenance building became a shop to work on steel coaster trains. And if you knew where to look along the back roads, you could find structures that were supposedly “ranger stations,” as well as, an old pond that the monorail once encircled.

The Kings Island monorail station in 1974.

Image via Paul K./KICentral.com

The monorail wasn’t Jungle Jim’s first or last purchase from Kings Island, though. Both within the grocery store and throughout its property you’ll find all kinds of Kings Island knick-knacks ranging from statues to decorations to vintage popcorn machines. Kings Island isn’t even the only amusement park they’ve sourced entertainment from, several of the store’s animatronic characters were relocated from the now defunct, local Americana/LeSourdsville Lake Park.

As for Universal Mobility Incorporated, their transportation systems never were put into use outside of light duty at theme parks and airports. They built their final monorail in 1984 for the Louisiana World Exposition. In 1989, a subsidiary of Bombardier (the multinational company known for large scale transportation projects, snowmobiles, aircraft, and at one time: military defense), purchased what was left of Universal Mobility. These days, only a few of the UMI systems remain. Monorails at Hersheypark, the California Exposition, and Zoo Miami still run, while remnants of their technological designs exist in part at the Tampa Airport and as a small circulator transit system in Jacksonville, Florida. The only other remaining full scale monorail: the one at Jungle Jim’s.

Jungle Jim's Monorail, June 2008.

It may have taken awhile and you may only get to ride it during special events, but it exists.

It’s there.

And it works.

Cincinnati abandoned its subway system, but the suburb of Fairfield gained a monorail. Restoring the ride was no small feat, either. It took time, engineering, and money to deliver the store another iconic, attention grabbing novelty. That’s Jungle Jim’s for you though, and it’s part of the experience and mystique of the world’s most impressive and interesting grocery store. A place that proudly bolsters its identity by re-purposing local history.

Update | Dec. 29, 2019:

Over the course of 2019, Jungle Jim's original monorail station and storage track were fully converted into event space. A new train maintenance facility was constructed adjacent to the station/new event space. The station now features a bar that specializes in bourbon and facilities that can be customized to different events. As of this update, the bourbon bar is open two nights a week to the public, serving only special events at other times. The monorail itself does not run regularly, but can be utilized as an option when planning events. To see updated photographs and learn more information, check out this story I put together for Cincinnati Refined.

The monorail station, event space, and bourbon bar as seen in December, 2019.