Cooper Stadium and Reflecting on a Relationship With Baseball

There was this scrap of paper that had been on the floor of my apartment next to the dryer for a few days. I never managed to pick it up until I finally had to do some laundry. I scraped it off the fake wood and for a second, I thought it was a sticker of some sort. When it came up, I turned it over and found the Major League Baseball logo. Which is odd, because I haven't been wearing any clothing adorned with MLB trademarks for some time.

|

| - The light towers and luxury suites of old Cooper Stadium overlooking Mt. Cavalry Cemetery. |

My “Est. 1869” cap and Aroldis Chapman jersey had been collecting dust in the closet. There’s an old Reds shirt I run in on occasion, but at the time I came across the floor-adhered logo, I hadn’t been putting in any miles. I was too busy. With life. With work. With other priorities. Things had been kind of drifting to the side. I’d say baseball was one of them, but that’s only partially true since baseball had been declining from my attention for awhile. I barely glanced up from my work laptop to watch the Dodgers and Red Sox go at it in the most recent World Series, but even if I had focused on the contest—I’d have to supplement the viewing experience by looking up player stats, rosters, and names just to try and remember who was who. It was the first baseball I had watched on television in 2018. I had caught a few Reds’ games on the radio over the summer, but I couldn’t take the subtle hints of annoyance in Marty’s voice anymore (that’s a knock on the team, not the hall of farmer). I made it out to the ballpark once in 2017, but that was a massive decrease from my peak of 30 regular season games and one playoff in 2010. I vehemently deny the label of “fair weather fan,” but let’s be honest: most people are to some extent, whether we want to admit it or not. It’s tough to stay invested in a 162 game season when there’s not much to root for on the field or look forward to in the future. The Reds’ have taken a fall from grace after shakily standing on a pedestal of moderate success at the onset of this decade. Even if they were playing exciting baseball under a manager I liked (adios, Bryan), I still don’t know if I would’ve made following the team much of a priority. Just the realities of attention spans, obligations, and competing interests. Every year I tell myself I’m gonna get back to checking the box scores, attending regular games, and reading about the team every day. Maybe in 2019, I actually will.

|

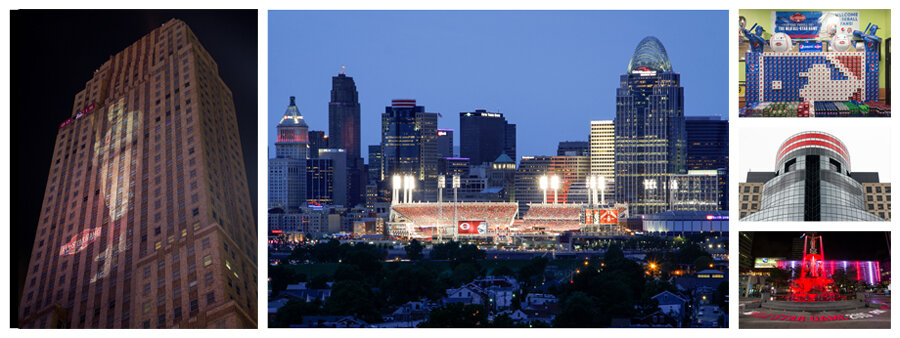

| - Shots from a series I did on the Reds hosting the 2015 MLB All-Star Game, when baseball was more of a priority. |

Now, I’m not intending for this piece to turn into a long winded rant about how my generation—the loathed, seemingly anti-baby boomer and anti-baseball scourge derided as “millennials”—is losing interest in “America’s Pastime” for that socialist sport across the sea known as “soccer.” But, I took an interest to football (the one with feet, not the hands) a few years back. I always wanted a local team to support and eventually had one. I’m involved with a lot of the environs that come with following that club. There’s a personal connection there and as the ‘men in orange and blue’ began capturing hearts and minds at Nippert Stadium: my free time, enthusiasm, and beer money followed. In FC Cincinnati, I found multiple things I had never found with the Reds. There will always be a love, respect, and passion for the local baseball club, but without realizing or intending—soccer took up what little time I had for following pro sports. And it gave back.

I want to get back to baseball. I will get back to baseball. At least I hope to anyways. It certainly wouldn’t hurt if Great American Ballpark had a more promising product to watch, but my love for that game isn’t just steeped in local pride and the team named for the color of their stockings. I love the strategy, the techniques, and most of all: I love the history. Even if my interest in on-field play has waned in recent years, my passion for the game’s past never has.

|

| - The lone Cincinnati Reds game that I made it out to in 2017. |

I’ve written about this before, how a professor I once had taught a whole class around the idea that the story of baseball coincides with our own, on multiple levels.

"Baseball mimics culture," he said.

We can tie the happenings of baseball to historic events, landmark moments, and even minutia on both personal and global scales. Baseball is wonderful, because of its past. It's truly a beautiful thing. Which brings me to a pot hole ridden road and overgrown lot in Columbus, Ohio—what used to be the outfield of a minor league ballpark. I’ve actually featured some photos of this old stadium before, back when it had only been abandoned and derelict for just three years.

|

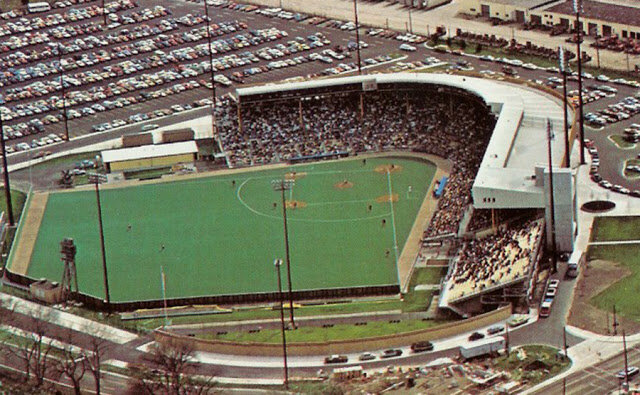

| - Columbus' Cooper Stadium as seen in 2011. |

It’s also not the first abandoned stadium I’ve written about on QC/D (that title goes to the glorious ballpark-turned-luxury-apartment-building in Indianapolis).

|

| - Bush Stadium in Indianapolis as seen in 2009. |

I was on a road trip to Cleveland and getting back into shooting with 35mm. I had budgeted all my film to be used on these frequent excursions up and down the state. I resigned myself to the idea that I would take different routes and only stop to shoot interesting things I came across. No set sights or plans, just spontaneity.

Then I remembered Cooper Stadium as I passed through Columbus and detoured directly for some baseball history.

|

| - The Columbus skyline as seen from the cemetery near Cooper Stadium. |

I arrived and made some photographs via both digital and film (which is why some of the images here look quite different from each other). The outfield fence and first base grandstands were gone. What was once the playing surface is now a free-growing field of vegetation. The third base grandstands, ticket offices, and light poles were all still there. The uniquely shaped “luxury” boxes added in the 70’s were mostly boarded over. From the main road, the stadium doesn’t look like much. On the other side, though, what’s left still has the appearance of a classic ballpark that attempted to turn modern.

|

| - Cooper Stadium, 35mm. |

If you pull into the cemetery nearby, the remains of the park still loom fittingly. Seats and all.

|

| - Cooper Stadium, digital. |

|

| - Cooper Stadium as seen from Mt. Cavalry Cemetery, 35mm. |

Columbus’ professional sports are mostly centered around the aptly titled “Arena District.” While the local soccer club hopes to build a new pitch in the area, current district tenants include The Blue Jackets of the NHL and the Columbus Clippers. A triple-A team one step below the majors that now serves as a development squad for the up-state Cleveland Indians, the Clippers have long been a local mainstay. They play their innings at Huntington Park, one of the finest facilities in minor league baseball (or so the reviews say). They’ve been in the Arena District since their new ballpark opened in 2009, during an era when even minor league teams have been able to secure public financial assistance for new facilities. The move came after 31 years at Cooper Stadium.

|

| - Cooper Stadium when active. Image via Wikipedia. |

“The Coop,” or “County Stadium” as it was once simply known, pre-dated the Clippers, though. It was built at a time when baseball was experiencing unparalleled popularity and growth across the nation. Even as the two major leagues were hesitant to expand, large cities and small towns alike yearned for ball clubs to represent them and entertain the populace. New teams in many lower leagues sprang up everywhere. Some were independent, but most were born in support of developing players for the big National and American League clubs. Like most top tier teams, the St. Louis Cardinals were eager to find markets for their prospects to play in.

|

| - Red Wing Stadium in Rochester, NY. Image via MiLB. |

The Rochester Red Wings organization made the jump to minor league baseball’s highest level (triple-A) by joining the International League in 1929. The team and their new ballpark (appropriately named “Red Wing Stadium”) were both owned by their parent club, the St. Louis Cardinals. A few years later in 1933, the Cards established another triple-A affiliate. The Columbus Red Birds took the field playing in the American Association at the all-new “Red Bird Stadium.” Destined to be known as “Cooper” and abandoned seven decades later, Red Bird Stadium was based on the same blueprints as Red Wing Stadium in Rochester.

|

| - Red Bird (Cooper) Stadium in Columbus. Image via The Clio. |

Located in the Franklinton neighborhood, Columbus’ new field was atypical of ballparks in the era—featuring a large grandstand covered by a flat roof, some uncovered overflow bleachers, room for expansion if there was ever a need, and classic light towers to deliver baseball at night (a concept that was established in the minor leagues, but wouldn’t come to the majors until the Reds installed lights in 1935 ). Red Bird/Cooper Stadium looked a bit different in its inception compared to its end, something more along the lines of old Crosley, Fenway, and Wrigley. It was a classic baseball “cathedral.”

As major league teams often do, the Cardinals reorganized their development system and minor league affiliations over time. The Columbus Red Birds were relocated to Omaha in 1954, replaced almost immediately by The Columbus Jets. With a new team and new identity came a new, but still direct, name for the local ballpark: Red Bird Stadium was now “Jets Stadium.”

|

| - The 1969 Columbus Jets. Image via the Columbus Metropolitan Library. |

Initially the feeder club to the then-Kansas City Athletics, the Jets were developing players for the Pittsburgh Pirates when the franchise relocated to Charleston, West Virginia at the end of the 1970 season. While the classic stadium in Franklinton had been the predominant sporting ground for forty years, organized baseball in the city dated back to 1894. Columbus was now without a team for the first time in 76 seasons.

For six years, "cowtown" went on without professional baseball. The Franklin County government stepped in and purchased the stadium, as well as, a new franchise from the International League. Rooftop luxury boxes were added in the architectural style of the era and despite the ballpark being outdoors, AstroTurf was installed (a common, yet unfortunate, trend of the times). In 1977, the Columbus Clippers took the field in a renovated park now known as County Stadium.

|

| - Cooper Stadium after receiving luxury boxes and astroturf. Image via The Clio. |

From the outside looking in, the place seemed to take on a new, modern appearance. But the classic concourses, concession stands, and poles supporting the roof remained. There was still a lot of charm sitting beneath those new amenities. The grandstand could seat around 11,000 local fans who developed a reputation for ringing cowbells in an effort to rally their team. The Clippers organization held a lengthy affiliation agreement with the New York Yankees. The list of talented alumni is incredibly distinguished. Melky Cabrera, Robinson Canó, Bernie Williams, Daryl Strawberry, and the legendary Derek Jeter are just a handful of standouts amongst past Clippers’ rosters. Bolstered by the deep pockets of ‘The Bronx Bombers,’ Columbus saw a lot of incredible ballplayers take the field and grace the locker rooms at County Stadium, which was eventually given the name Cooper Stadium.

Harold Cooper had grown up in the Franklinton neighborhood. His grandfather helped build the stadium that would eventually be named in honor of his grandson. As a kid, Harold worked odd jobs around the ballpark for the Red Birds organization (one such task allegedly included scraping mold off hot dogs). He served the US Coast Guard in World War II and became a minor league baseball executive after his service. Cooper eventually spearheaded the effort to bring the Jets to Columbus and returned to his hometown to run the business side of the team. After stepping back from baseball, the man entered local politics, serving as Franklin County Commissioner for 17 years. He was one of the power players in 1977 who persuaded the county to purchase the stadium and a new team in an effort to bring baseball back to the city. He also served as President of the International League for over a decade. Dubbed “The Father of Columbus Baseball,” Harold had twice brought the game back to his hometown and helped it prosper at the highest possible minor league level.

Although Major League Baseball teams existed in Cincinnati and Cleveland—just a few hours away in either direction—it wasn’t too “out there” to think Columbus and its strong baseball culture might enter the discussion of expansion. The city was absent from the list of teams for a proposed, third major circuit known as the Continental League, but as the culture surrounding the Clippers grew, Columbus kept appearing on baseball’s radar. I’ve heard multiple times that local businessman and philanthropist John H. McConnell was once actively looking to lure MLB into the city. Once a minority owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates organization, McConnell sought to deliver pro sports to a major city that lacked any top tier teams. While his baseball ambitions never quite panned out, McConnell was still an early investor in the Crew SC soccer team and was also the man who delivered the National Hockey League’s Blue Jackets. Columbus still comes up on speculative MLB expansion lists from time to time, but whether or not the American or National Leagues land there, the Clippers tradition started by Harold Cooper held strong, even after the Yankees broke off their affiliation at the end of 2006.

In 2007, National League style ball returned to the park. For one season, the former-Montreal-Expos-turned-Washington-Nationals sent their prospects to Cooper. A dismal year of being backed by a dismal parent club didn’t seem to damper spirits much, though, because a new chapter and a new facility was on the horizon. The final baseball game at Cooper took place on September 1, 2008 in front of over 16,000 fans.

|

| - A game at Cooper Stadium in its last days. Image via The Clio. |

Ballparks have long been called “cathedrals,” recognition of their significance in both sporting history and American culture. The phrase is typically reserved by purists for the more revered and historic structures, but it also gets thrown around pretty casually to describe brand new buildings or the quaint stands of beloved lower league locations. Often, the sagas and stories of stadia can outshine the play on the field. The ballpark itself is just as much a part of the game as the pitcher, manager, and mascot. Several great websites chronicle and document American ballparks from methodical benchmark breakdowns to romantic reviews of the sights and sounds. When it comes to Cooper Stadium, perhaps Ballpark Digest painted the picture best:

...a game at Cooper Stadium is like stepping into a time machine. One of the oldest ballparks in North America still in use in affiliated ball (it opened in 1932), Cooper has added a few modern amenities like rooftop suites, a picnic area and some between-inning activities. But the main gist of a visit here is to experience old-time baseball in an old-time setting with old-time values. It is not hard to sit down, close your eyes and envision Nick Cullop hitting one of his 22 triples in 1933, Harry Brecheen sneaking strike three past an unsuspecting hitter or Willie Stargell flogging a shot into Dysart Park behind the right fence. Listen closely and you might hear Jack Buck, who began his Hall of Fame career as the team’s broadcaster in 1950, call the game in his wry, humorous fashion.

Even with “modern” upgrades during the days of disco, “The Coop” retained its charm and historic aesthetic under the roof and in the concourses. As someone who never found his way there, that makes me feel even worse for missing out. The place seemed truly unique and special. The Clippers began play at a new downtown ballpark in 2009. The likeness of Harold Cooper was erected out front, but across town, the lights were out at the old county park that bore his name. Harold passed away in 2010.

|

| - Cooper Stadium, digital. |

Maybe it’s fitting that an auto racing track was proposed to replace the stadium’s baseball tenant. That’s happened at closed ballparks before such as Indianapolis’ Bush Stadium and Baltimore’s Westport Stadium. The layout makes for a seemingly easy conversion. You essentially already have the biggest piece of needed infrastructure in place: the grandstand.

The proposed concoction of a small, paved racetrack that would be tied to a “research center,” hotels, event space, restaurants, and other generic selling points used to line press releases had generated some buzz and opposition from noise wary locals. Portions of the stadium were demolished in anticipation of the motorsports park, but the project is now believed to be dead.

|

| - Cooper Stadium, digital. |

These days, the Clippers’ new home is well reviewed, well attended, and situated near other downtown Columbus institutions. Aside from appreciating the writing of others and staring into the grandstand across an overgrown lot, I never had the chance to know the previous stadium. But, there’s something to be said about older parks and the way they told the story of baseball, a sport that’s always evolving. If you’ve got a memory from the days of Cooper, I'd truly love to hear it (shoot me an email or leave a comment below).

Baseball’s rise spawned the creation of parks all across the nation. Some survive, others died off, many were replaced by contemporary versions that carry the tradition. These days, soccer is often acknowledged as the next game to grow in America, taking over just as baseball once did. Interestingly, ballparks have helped usher in this notion as well.

|

| - Cooper Stadium, 35mm. |

Temporarily converting a baseball park to accommodate association football isn’t at all unheard of. The historic New York Cosmos called old Yankee Stadium home for a time and today, new Yankee Stadium hosts New York City FC (to the chagrin of many). It’s the minor league ballparks that are doing the heavy lifting, though, just as they once helped proliferate baseball. The sightlines aren’t always the best, but these stadiums offer a way to get soccer clubs off the ground in certain markets. In 2018, over one quarter of the USL Championship’s 33 teams called baseball stadiums home. A tenth USL team, the Tampa Bay Rowdies, play in a former ballpark now solely dedicated to soccer. The Las Vegas Lights will follow suit with a ballpark conversion of their own when their bat wielding roommates depart. And there are even more soccer leagues currently being established at various levels, many of their teams taking up residence on baseball fields as well. For 2019, three of the USL Championship’s seven expansion clubs will also kick off in ballparks. The ubiquitous baseball cathedral continues to plot the course of professional sports in the United States, now for more than just one athletic venture.

What remains of Cooper Stadium, however, won’t find a savior in lower division soccer. Columbus is already host to a top tier soccer club playing at its own venue (with plans to build an even newer stadium close to the other pro sports action in Downtown). With the racetrack out of the picture, it’s not presently clear what will happen to the last vestiges of the historic ballpark. Although baseball still enjoys a proud tradition in the city, what’s left of the old County Stadium that was renamed for the “Father of Baseball in Columbus,” sits quietly—dramatically looming over an empty field next to a cemetery.

|

| - Cooper Stadium and Mt. Cavalry Cemetery, digital. |