Cincinnati's Subway

It was a good thing we were packing. We had our high powered flashlights and then some extras. It was pretty dark as we stepped onto the station platform. It seemed almost as if the power had gone out or if there weren't any lights installed at all. We traded jokes and conversation as we waited for our train. Cincinnati isn't really known for its subways. The stations are dark, cold and covered in dust and frankly the service is terrible. We waited on the platform for forever and not one single train ever came.

In case you can't detect sarcasm, I was being facetious in the first paragraph. No, we weren't really waiting for a train to come and whisk us away on the Cincinnati Rapid Transit Subway Line, because there isn't one. Well there is, and there isn't. Cincinnati's abandoned subway tunnels are often the subject of local urban legend. Most don't know about them and those that do don't really have a clue as to what they're talking about. While Cincinnatians go about the city via their car or bus, as those are the only current transportation options, most don't realize that the rail network they could've had is right below their feet, in a catacomb of future potential.

|

| - A lengthy, curved section of the subway tunnels. |

You may remember last year when Queen City Discovery was provided the awesome opportunity to see a section of the Cincinnati Subway. The history of the subway is covered in greater detail in that article. However, in short, the subway was constructed following two public votes. The plan was to drain and replace the Miami-Erie Canal with an underground rail line and a new road built on top of it, today that road is known as Central Parkway. The two miles of abandoned tunnels would've been part of a larger 16 mile loop around the city. Planning began as early as 1905 with construction starting in 1920. By 1925 construction came to a halt and despite several attempts to revive the project, local politics and world events would all be contributing factors in bringing the subway to its current state (again, see last years article for a more detailed history). Had the Cincinnati Rapid Transit System been completed, residents of the Queen City might be catching similar trains in similar looking stations like the ones seen below in Chicago.

|

| - A heavy rail car on Chicago's Red Line as seen during a trip there a few months back. |

It's both amazing and frustrating to think how close Cincinnati was to having rail transportation. Cincinnati would've joined the ranks of Philadelphia, Chicago, New York and Boston as the only cities to have rapid subway lines before World War Two. Undoubtedly, a completed subway would've had profound social, cultural and economic effects on the city still today. While we're left with only highways and roads to commute and travel through the region, its fascinating to think how transportation in this area could've possibly benefitted from the subway. Although they never saw a single train or passenger, the 80 year old tunnels beneath the city streets still hold great potential for the future.

|

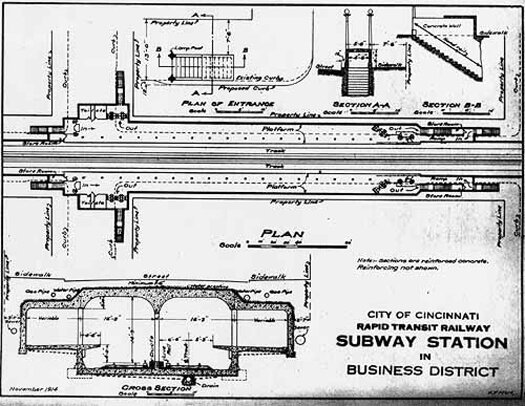

| - Early subway plans. Of the four underground stations, only the one at Brighton's Corner really resembles this design. Photo credit: Cincinnati Transit. |

|

| - An excerpt of the above plans shows what a pedestrian entrance to the subway might have looked like adorned with light posts (left), similar to the ones seen in Chicago (right). |

A 2008 study by the URS Corporation found the tunnels to be in relatively good shape, despite being over 80 years old and the slight wear they've incurred over the years. Parallel solid oak beams of wood remain in the tunnel centers, still waiting for the rails they never received. Over the years the subway tunnels have been re-purposed to house a secondary water main, fiberoptic and power lines, and even a civil defense fallout shelter. In their life span the tunnels have held up remarkably well to vandals and water that has leaked through their cracks. Despite the adapted uses found for the tunnels since the abandonment of the rapid transit project, the city of Cincinnati has maintained them in hopes of one day finally using them for a light or heavy rail transportation network. Today nearly two miles of tunnels and four stations remain hidden beneath Central Parkway.

|

| - Standing in the center of the track for inbound trains at the Brighton's Corner station. |

The Brighton's Corner station (seen above), most closely resembles the plans seen at the bottom of photograph number four. As we stood on the station platform, scanning it with our flashlights and cameras, it was eerie to think about what could've been. All the stations lacked were some tile work along the walls, modern amenities, lighting, plumbing and of course the trains. While not exactly the same, the Brighton station reminded me of Chicago's Red Line, which I had ridden just a few months ago.

|

| - View of the surface above where the Brighton station is located. |

|

| - Concept art from the 2008 URS report that shows what a modern station at Brighton's Corner might look like. |

|

| - The water main as seen from the Brighton station platform. |

Our flashlights looked like lasers cutting through the total darkness and dust of the tunnels. Walking between stations, it became apparent as to why someone thought to plan for a rapid transit system, it takes quite a bit of time to walk the length of this underground monolith. Mohawk's Corner, where Linn St. and Central Parkway connect, is the site of another station. Unless you've been reading up on your history, the casual urban explorer might walk right past it. The Linn St. station was sealed up, this is assumed to have once been the plan for preserving all of the stations. What remains of the station behind the cinder blocks is unknown.

|

| - The sealed up station at Linn St. |

While the 2008 study found the tunnels to be in good shape and the city has maintained them over the years, deterioration is present. Water often finds its way down to the subway via vents that had connected the tunnels to the surface. Over time, the water in certain sections has eroded and rusted away at the vents and their steel ladders.

|

| - Deterioration of a subway vent. Unlike this one, many of the others are very much intact. |

Trying to preserve the high powered flashlights for photograph exposures, the LED glow of my Mini Maglite flashlight made the dirt floor of the tunnels seem gray. The almost lunar looking surface became riddled with the first footprints it had seen in a long time as we traveled a path meant for trains. We approached the third and maybe most interesting station, the Liberty St. station. At some point during the height of Cold War era paranoia, this station had been converted into a nuclear fallout shelter.

|

| - The Liberty St. station. |

Would it really have protected anyone from the blast of a nuclear bomb or the subsequent radiation? That's debatable depending on who you talk to or what you read. It's unclear of how safe the shelter would've been just an estimated 20'-30' below the surface.

|

| - Stairs that would've connected the Liberty St. station to the surface. |

A booth constructed in the center of the station platform is often labeled by many as a fare/ticket booth, but given it's cinder block construction similar to that seen at the Linn St. station and the ventilation shafts connected to it, I think it may have served as part of the fallout shelter. John Palmer, a friend of mine, recalls the shelter having been stocked at least until the 1980's. He had once worked for ADT, who had installed an alarm on the shelter to keep out vandals. He was once called in to service the alarm while the city was in the process of removing the ration and water cans that had been stored in the shelter.

|

| - Liberty St. station platform. |

Industrial lights and chain link fence had been installed as part of the station's furnishings, while bunk beds void of mattresses still remained. How many could the shelter have housed in the event of a nuclear attack on the United States? Out of that number, who knew about the shelter and who got to go?

|

| - Concept art from the 2008 report showing what a modern Liberty St. station might look like. Note the glass windows jutting out just like the booth in the above photos. |

Further down we came to the Race St. station after a very long walk. This station is by far the largest of the remaining four. At its widest point, it's three tracks wide. The platforms are in an "island" format, surrounded on each side by parallel tracks and even feature "stub tracks" that would've housed interurban trains and trolleys from the outlying suburbs and neighboring cities.

|

| - A section of the Race St. station. Known as an "island" station, this platform is flanked by an inbound track at left and a stub track seen at right. |

Large concrete staircases would've allowed passengers to come to and fro the center of Central Parkway, putting them right between the central business district of downtown and Over the Rhine, which at the time of the subways construction was one of the most dense neighborhoods in the city. The station platforms are long enough to have housed two stopped trains each. Combined with the stub tracks, a total of six trains could've parked here at one time.

|

| - Sealed off stairs at the Race St. station connecting to the surface. |

|

| - Concept art of a completed Race St. station from the 2008 report. |

Given its large size and central location, its pretty reasonable to assume the Race St. station would've been one of, if not the main hub for the city's rapid transit line.

|

| - One of two "stub tracks" seen at the center of the Race St. station. |

East of the Race St. station, the three tracks merge back into two. Plans called for the line to then turn south beneath Walnut St. and head further into downtown, with an eventual station beneath Fountain Square. Just as the tunnel begins to turn beneath Walnut St., it comes to an abrupt halt, ending in a brick wall.

|

| - The brick wall, ending the tunnel near Walnut St. From here trains would've headed through downtown towards the riverfront. |

As the streets of downtown descend in elevation towards the riverfront, the Cincinnati subway would've continued at grade and emerged from beneath the streets onto an elevated rail line, similar to the "EL" in Chicago.

As we made retraced our tired steps back out of the subway tunnels, it was hard not to ponder and think about what could've been, what impact the subway and passenger rail would've had on the city. The tunnels hold a great potential for the future of this city if ever utilized for their true purpose. I've seen first hand an opportunity that Cincinnati shouldn't miss. Beneath our streets is a great resource for moving not only the city, but the region forward in terms of transportation and economic development. I grew up dreaming about exploring Cincinnati's Abandoned Subway until I finally saw it for myself. Maybe one day someone else will grow up dreaming about those guys who explored the subway, back when it was abandoned.

-Gordon Bombay

As we made retraced our tired steps back out of the subway tunnels, it was hard not to ponder and think about what could've been, what impact the subway and passenger rail would've had on the city. The tunnels hold a great potential for the future of this city if ever utilized for their true purpose. I've seen first hand an opportunity that Cincinnati shouldn't miss. Beneath our streets is a great resource for moving not only the city, but the region forward in terms of transportation and economic development. I grew up dreaming about exploring Cincinnati's Abandoned Subway until I finally saw it for myself. Maybe one day someone else will grow up dreaming about those guys who explored the subway, back when it was abandoned.

-Gordon Bombay

|

| - A few of "Cincinnati's 8th Precinct." From L to R: Gordon Bombay, The Boy Scout's Roommate, Billy Valentine, Dr. Venkman, Lance Delune and The Boy Scout. |

- For Dr. Venkman's take on our subway exploration, check out his piece.

- For more subway photos and a more detailed history check out Queen City Discovery's previous article.

- For the best historical and technical resource on the subway, check out Cincinnati Transit.

View all of the QC/D subway stories over the years.

Updates | Oct. 16, 2017:

- As of this update, there are still no plans for realizing the Cincinnati Subway.

- Awhile after this article was published, I learned about how a section of Boston's Red Line served as the basis for the Cincinnati Subway. I finally got to visit the Red Line in 2017 and get a glimpse of what we could've had. That story is here.